When I was in secondary school, life seemed so simple: wake up, go to school, sit for classes, study for tests…

However, the high school experience has been very different for my youngest sister. Instead of waking up early to take the bus, she stumbles out of bed five minutes before her class starts. Her lessons are all done through a screen, her homework needs to be printed out and even her tests have had to change since the students can’t sit in an exam hall without access to phones or computers.

For millions of kids all across the country, the effects of this year will be felt throughout the rest of their lives. With schools closed and extra-curricular activities limited, many students have been struggling to adapt to their new virtual learning curriculum.

But in a way, my sister and those like her can actually be considered the lucky ones. Sure, their schooling sucks, but at least they’re getting an education.

What about those who don’t even have that?

How Many Kids Can’t Go to School?

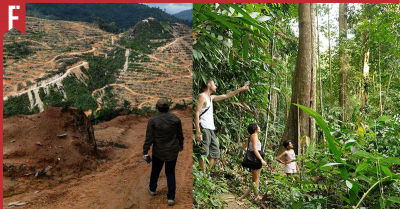

Today, it is estimated that there are thousands of kids all across the country who lack access to basic education. These consist mainly of children from refugee families, most of whom have been denied access to the formal education system even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to reports from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are a total of 150,379 people of concern living in Malaysia today. Out of this number, 23,823 of them are old enough to be in school.

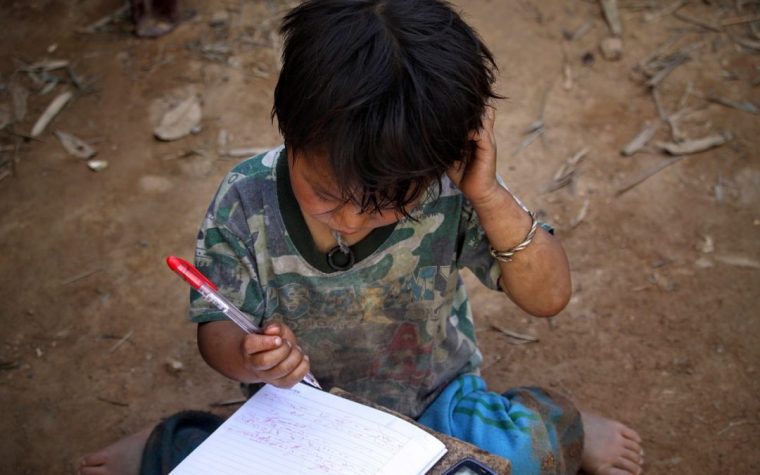

As they aren’t allowed to attend regular schooling, many refugee children rely on an informal parallel system of community-based learning centres. But even before the events of this year, far too many of them were falling through the cracks.

When it comes to schooling, it is estimated that:

-

14% (1,234) of refugee children aged 3-5 years enrolled in pre-school education

-

44% (5,046) of refugee children aged 6-13 years enrolled in primary education

-

16% (874) of refugee children aged 14-17 enrolled in secondary education

This means that even in a best case scenario, more than half of them — potentially thousands of children — have not been able to get the education they desperately need.

Where Do You Learn If You Can’t Go to School?

To answer this question, we spoke to Angelina, an Academic Volunteer with six years of experience at the Manna House Learning Centre (MHLC).

Established with the help of UNHCR, Manna House is one of the few places in Malaysia where refugee kids can get an education.

“It originally started out as a home learning centre, back when there were just a few kids,” Angelina explained. “When we grew bigger, we managed to get a free place from a nearby church, so we used their premise. At that point, we had about 20 kids.”

Today, Manna House has about 80 kids, and the numbers are still growing.

What Makes a Learning Centre Different from Normal School?

Well, for one thing, they don’t have actual teachers. Instead, learning centres such as Manna House rely heavily on volunteers like Angelina to get things done.

“As a volunteer, you kind of have to do a bit of everything,” she said. “You teach, you manage the timetable, cleaning duties and even sometimes take care of the kids when they get sick. But my main duty is to plan the academics and teaching duties, and that’s what I enjoy the most.”

But without proper full-time teachers, even those kids who are lucky enough to access a learning centre may struggle to progress.

“In terms of quality of education, I think that it will vary a lot between centres,” said Angelina. “Because we don’t have a standardised set of syllabus, it really depends on what you can teach, what kind of resources are available… even the language of instruction. Only a very small number of learning centres will have the kind of quality education that the kids deserve.”

“There should be more hours, there should be more teachers. But having said that, the kids also face a lot of challenges at home.”

The COVID-19 Pandemic has Only Made Things Worse

Just like thousands of schools across the country, Manna House had to temporarily shut down when the MCO was announced. Unlike the official schools, refugee students and learning centre volunteers have been left to fend for themselves.

“The first time round when the MCO was announced, we were actually taken by surprise. We were totally unprepared,” said Angeline. “In fact, it happened during our first semester break in March. We got an email telling us to extend our holidays and advising us to stay closed for an extra two weeks. And after that, the government implemented MCO, which meant that we couldn’t go out. But we were determined to make sure that our kids would not lose out on their education.”

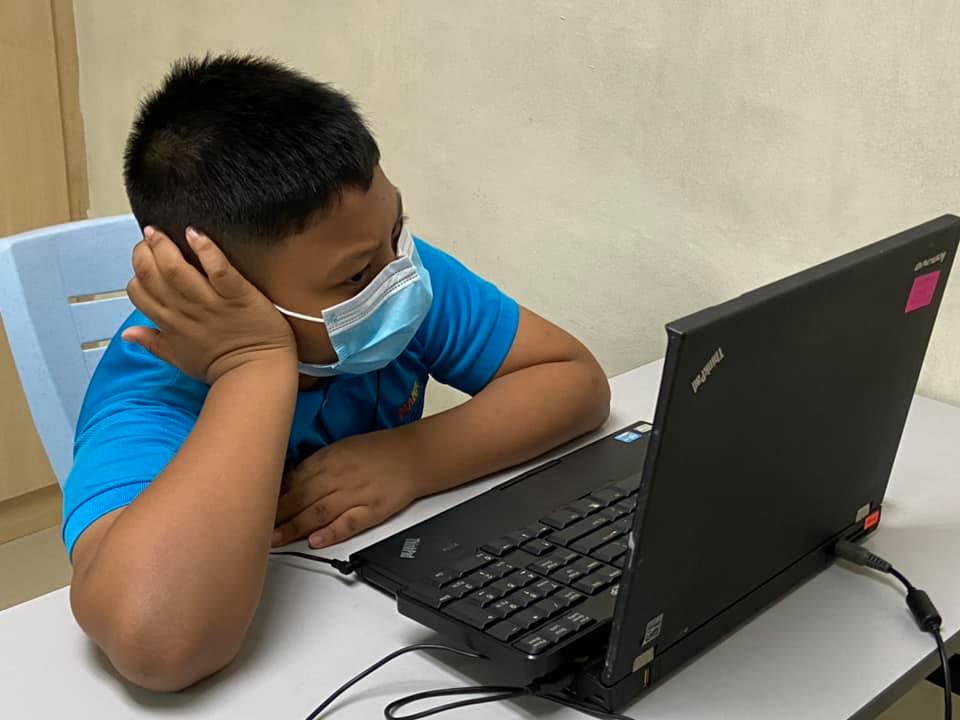

While regular schools were able to set up online learning and virtual classes, things were not so easy for refugee learning centres. Virtual learning was a challenge since only a few of their students had reliable access to computers or the internet.

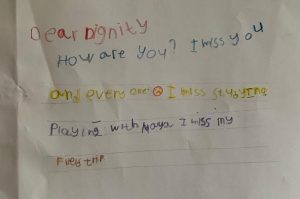

“In the beginning, there was very little we could do in terms of holding classes,” she explained. “So what we did was basically WhatsApp the homework to them, then ask them to take a screenshot of the finished work and send it back to us for marking. The process was really tedious.”

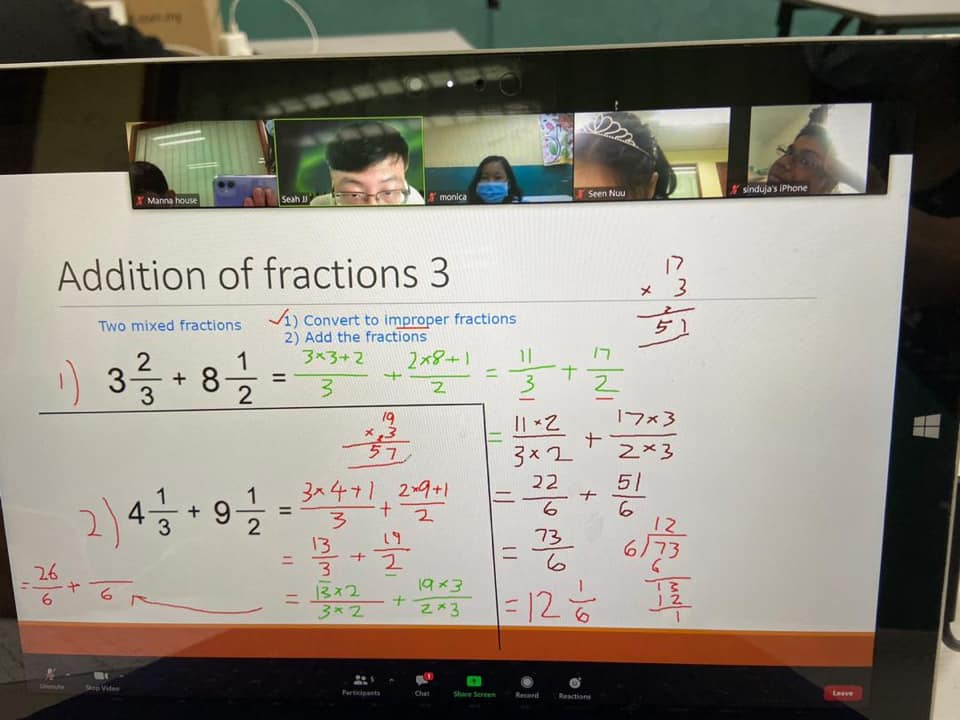

Over time, they were able to switch to a Zoom model, with students borrowing their relative’s phones or computers in order to attend classes. But even that had several problems.

“A lot of our permanent volunteers are older people, aged 50-plus. So during the MCO and RMCO months, most of them opted not to come back,” Angeline said. “Many of them were also not familiar with technology like Zoom, so they couldn’t teach.”

“What really saved us was that we had a lot of university-aged volunteers who were really really good and could teach through Zoom. With their help, we were able to set up classes and get through our curriculum.”

But Even With All This Effort… Is It Worth It?

Even with the volunteer’s best efforts, refugee centres cannot replace actual schooling. Without access to a formal education, many refugee kids will not be able to sit for important tests or receive the certifications needed in order to go to university.

“It’s very upsetting,” admitted Angeline. “Education should not be a privilege, it should be the right of every child. A lot of our kids are so capable, but because they’re not able to go through the proper channels, they’re missing out on the opportunities that all the other kids their age receive.”

“However hard they work, they will never be able to become a doctor or engineer or scientist… all the things that require proper certification.”

In fact, many of Angeline’s fellow volunteers are shocked to learn that the kids they’re teaching are unlikely to ever go to university or get a professional job.

“One of my volunteers actually confronted me about this issue in the past,” Angeline recalled. “She was quite taken aback about the fact that our kids could not access proper education here. She was asking me ‘What good will it do if they come to learn but can’t get the certifications they need?’”

“To me, basically it comes down to the fact that any education is better than no education at all.”

Every Child Deserves an Education

Even without certifications such as UPSR or SPM, Angeline firmly believes that the kids she teaches will be better off compared to those who weren’t lucky enough to get any education at all.

“Our kids came from families that have very little education,” she said. “A lot of them have parents who never went to school. They can’t speak English, some of them are illiterate… so our kids already have one leg up. We have to look long-term — even if the government doesn’t recognise refugees, being able to speak and read English will at least help them to get better jobs.”

Education is about more than sitting for tests. For thousands of children living in Malaysia today, education represents their best chance of breaking out of the cycle of poverty and becoming a contributing member of society.

For refugee families, schools represent more than just a place to learn — they are a safe haven. Children who are going to school are less likely to get involved in unsafe activities such as gangs, child labour or teen pregnancy. They have a chance to develop not only academic knowledge but also learning and social skills that will help them throughout their entire lives.

But Why Should We Care?

“Why should we worry about refugee kids?” some may ask. “After all, we have so many Malaysian kids who already need help. Why should we spend our time and resources on children who weren’t even born in our country?”

If I had to answer, I’d say that an educated population benefits all of society.

In this globalised world, the more educated people a country has, the more productive its economy becomes. Educated workers lead to faster economic growth, which is something that benefits us all.

Without education, refugee children are vulnerable to a wide range of issues including unemployment and exploitation. Without opportunities some are more likely to turn to crime out of sheer desperation. But even those who stay on the straight and narrow are often stuck in low-pay, low-skill jobs, forcing them to continue the cycle of poverty for another generation.

Instead of forcing them to remain stuck in a poor, easily-exploited underclass, wouldn’t it be better for everyone if refugees could become contributing members of society?

Extending a Helping Hand

Like it or not, we can’t just ignore our country’s refugee population. We can’t just pretend that 150,000 people don’t exist, even if they aren’t citizens of Malaysia.

Despite what some may assume, the vast majority of refugees don’t want to be living on government or charity money forever. While they may not speak our language or fit into our culture, all of these refugees came into our country hoping for a better life without war or instability or natural disasters.

Instead of casting them out or ignoring them, we should extend a helping hand. Providing access to education may seem like a small thing on our end, but for Malaysia’s refugee population, it can be their only hope of escaping a life of violence or poverty.