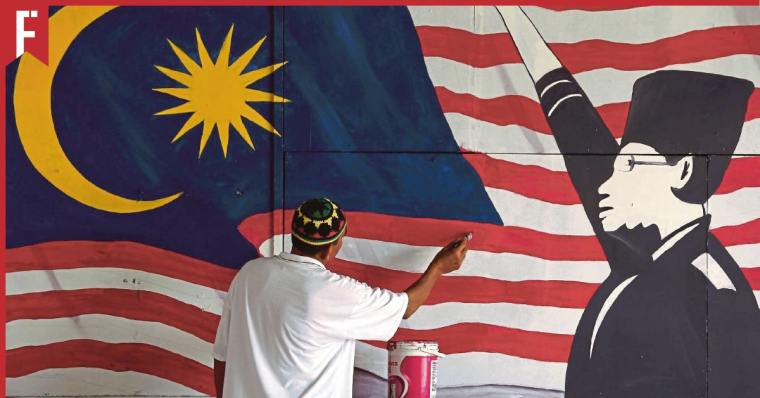

The year is 1957, and the newly-independent nation of Malaya has just taken its first steps onto the world stage. Before a crowd of 20,000, Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman leads the celebration with his cries of “Merdeka!”, cementing Malaysia’s most historic moment of all time.

Tunku had already overcome many challenges in order to reach this point. But he would have to face many more in order to transform the country from the “Malaya” of the past to the “Malaysia” of the future.

Challenge #1: The First Emergency

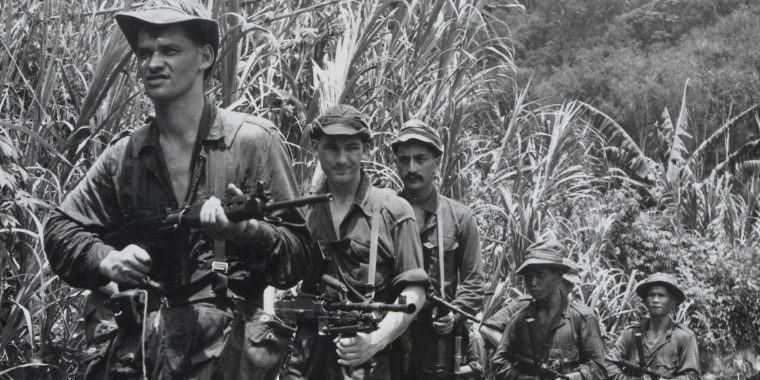

The first challenge was something that the nation had been struggling with shortly after the end of World War Two. Between 1948 and 1960, Communists insurgents led by veteran guerilla leader Chin Peng launched a rebellion — first against the British, then against the Malayan government.

At their peak, it is believed that the self-proclaimed Malayan People’s Liberation Army (MPLA) had an army of more than 13,000 guerillas hiding in the thick jungles of Malaya — most of them Chinese. They launched many attacks during their insurgency, culminating in the assassination of British High Commissioner Sir Henry Gurney in October 1951.

However, the Communist’s greatest success was also the key to their downfall. Although they claimed that the assassination was a key victory, such terrorist tactics shocked and horrified many ordinary Malayans. Recruitment fell sharply as Chinese communities withdrew their support.

Most of the Communist army would surrender by 1989. Although Chin Peng and a die hard group of fanatics would remain in hiding, they would never again have the strength to take over the nation.

Challenge #2: Building An Economy

At the time of its independence, Malaya was actually a fairly rich country due to our valuable natural resources. In fact, Malaya was considered a world leader in the production of rubber, tin, palm oil and iron ore.

However, while these export industries provided our starting government with a healthy flow of cash, Tunku knew that becoming overly reliant on agriculture would be risky. Having lived through fluctuating food prices during the Japanese Occupation, he knew just how important it was to build up a strong, resilient economy.

Tunku was also keenly aware that Malaya’s advantages wouldn’t last forever. As synthetic rubber became cheaper and cheaper to produce, the price of natural rubber began to fall — a potentially disastrous situation as a large number of rural Malayans were still reliant on the rubber plantations.

In order to mitigate these problems, Tunku helped to establish the First Malayan Plan (1956 to 1960) and Second Malayan Plan (1961 to 1965), focusing on stimulating economic growth by heavily investing in industrial sectors. They also repaired critical and expanded infrastructure such as roads and ports that had been left neglected due to the Japanese Occupation and the Emergency.

Challenge #3: Creating a United Country

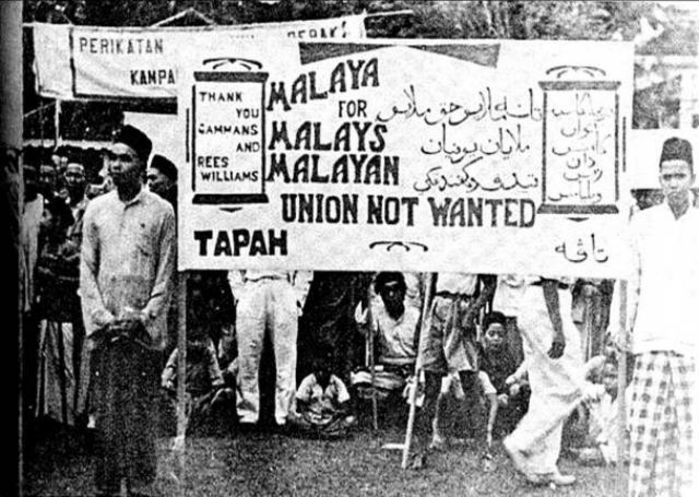

When it first became independent, Malaya consisted of only Peninsula Malaysia. Singapore had already achieved autonomy back in 1955, while the Borneo states (what we now know as Sabah and Sarawak) remained as British Crown Colonies.

However, in April 1961, Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew approached Tunku with an ambitious idea: the formation of a united country called “Malaysia”.

Although Tunku was initially skeptical, he would warm up to the idea over time. He believed that establishing a central government would make it easier to track down and combat any remaining Communist insurgents.

Singapore was especially singled out due to its large Chinese population. Tunku feared that if Singapore was allowed to remain independent, it might become a base for Communists insurgents.

After many tense negotiations, it was agreed that Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore would unite into a single country called Malaysia. The initial date was of the union was 31 August 1963. However, due to several factors, Malaysia would not officially come into being until 16 September — a date we now celebrate today as Malaysia Day!

Challenge #4: Foreign Relations

The main reason why the unification of Malaysia was delayed was due to the interference of foreign nations. Specifically, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Indonesia claimed that Malaysia was a form of “neocolonialism”. They basically believed that the whole idea was an attempt by the British to sneakily retake control of the region.

The Philippines, on the other hand, objected to the formation of Malaysia because they claimed North Borneo was their own territory.

To deal with these claims, the United Nations (UN) sent in a team to confirm whether or not the people of Sarawak and North Borneo truly wanted to join Malaysia. As you might expect, the UN team eventually dismissed the Indonesian and Filipino claims, allowing Malaysia to officially unite.

Unfortunately, this was not the end of our foreign policy problems. Although the Philippines reluctantly agreed to put aside their objections, the Indonesians had… other plans.

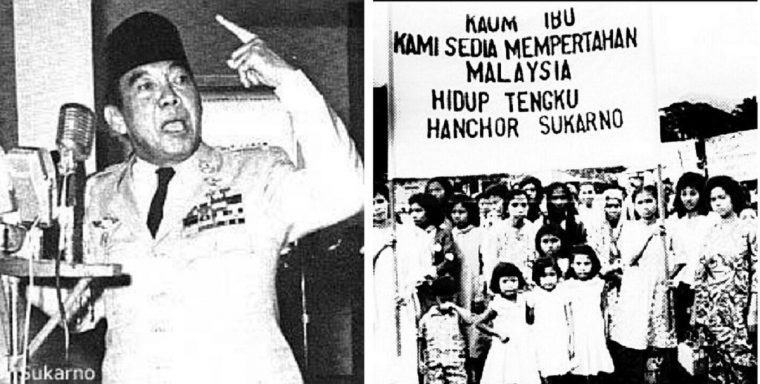

After learning that the unification would still go through, Indonesian President Sukarno denounced Malaysia as a “neocolonialist plot” against his country. He declared that he would launch a “ganyang Malaysia” (“crush Malaysia”) campaign and began sending troops into Sarawak.

This was the start of the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation — better known today as the Konfrontasi.

Challenge #5: Racism

As if all of these challenges weren’t enough, Tunku still had to deal with the biggest problem of all: racism.

At the time of independence, the population of Malaya was dominated by three different groups: the Malays (55%), the Chinese (35%) and the Indians (10%).

However, because Singapore’s population was Chinese-majority, adding it to Malaysia increased the Chinese proportion to around 40%, which upset many of the original Malayans. To avoid unnecessary conflicts, Malaya’s UMNO party and Singapore’s People’s Action Party (PAP) both agreed “not to compete in each other’s areas“.

Unfortunately, such cooperation would not last long.

The main conflict came from UMNO’s “bumiputera first” policies. UMNO believed that such policies were needed to help the poorer Malays compete against the wealthier Chinese. However, the PAP opposed such policies as unjustified and racist.

The original solution that Tunku proposed was to have PAP work up with UMNO to jointly run the federal government. Unfortunately, the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) opposed it because they saw the PAP as a threat — the PAP were not only another Chinese-majority party, but they were also seen as more radical, ideologically.

This racial tension would eventually expand across the rest of the newly-unified Malaysia.

Why Did Singapore Split From Malaysia?

Shortly after the unification of Malaya and Singapore, racial tensions between the Chinese and Malays started to burn out of control. Malay newspapers such as Utusan Melayu began spreading propaganda against the PAP, while the PAP in turn accused UMNO and MCA of deliberately inciting racial riots.

The final straw came during the 1963 state elections when Singapore UMNO (SUMNO) announced that they would be competing against the PAP. Though they failed to win any seats, the PAP were enraged as such an action went against the non-competitive deal that they had made with UMNO’s leadership.

In response, the PAP took part in the 1964 Malaysian federal elections. They joined as an opposition party, competing against UMNO under the slogan “Malaysian Malaysia”. Despite their best efforts, the PAP only won one seat with 2.05% of the vote.

However, UMNO’s leaders were incensed by the fact that the PAP had managed to win any seat at all. Negotiations between the two parties broke down, and it was soon clear that cooperation would no longer be possible.

On 7 August 1965 — just two years after their unification — Tunku asked Malaysia’s Parliament to vote on a resolution to have Singapore expelled from the Federation. He urged the Parliament members to vote “yes”, saying that Malaysia should “sever all ties with a State Government that showed no measure of loyalty to its Central Government”.

In response, Singapore announced that it would be leaving of its own accord. The separation became official just two days later, on 9 August 1965.

The Fall of Tunku

Although he was still beloved as Malaysia’s Father of Independence, Tunku would never manage to win his battle against racism.

His belief that every race should have their own political party to represent their interests proved insufficient to quell the dangerously rising tensions between the Chinese and Malay communities.

In the end, these tensions erupted during the 1969 general election — an event known as the 13 May Riots.

Despite his best efforts, Tunku was unable to prevent the bloodshed. In the aftermath, he found himself sidelined in favour of Deputy Prime Minister Tun Haji Abdul Razak bin Dato’ Hussein.

This Story Sounds Strangely Familiar…

Despite all that he had done for this country, Tunku’s career ended with a whimper rather than a bang.

Shortly after the 13 May Riots, Razak established the National Operations Council (NOC).

Officially, they were merely an administrative body focused on ending the racial riots and restoring law and order throughout the country. Unofficially, the Parliament was suspended due to the emergency situation, allowing the NOC to more or less run the country from 1969 to 1971.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Tunku was forced to resign. Razak would replace him and become Malaysia’s Second Prime Minister on September 1970.

However, no matter how hard he tried, Razak was ultimately never able to completely replace Tunku. Even to this day, Tunku is known and respected as the Father of Independence.

If you’re interested in learning more about how Tunku led our country from a colony to independence, check out:

Today In Malaysia: On The Road to Independence