The year is 1941. World War II is in full swing.

In Europe, Hitler’s forces have just launched their sudden but inevitable betrayal against Stalin in a devastating invasion that would take over vast swaths of Soviet territory.

In the east, the Japanese launched their own surprise attack against Pearl Harbor, giving the Americans a metaphorical kick in the balls which they would very soon come to regret.

But as significant as those events are, they’re not our focus today. Instead, let us focus our attention on a battle that took place much closer to home: the Japanese invasion of Malaya.

Why did the Japanese Attack in the First Place?

To put it bluntly: they wanted our stuff.

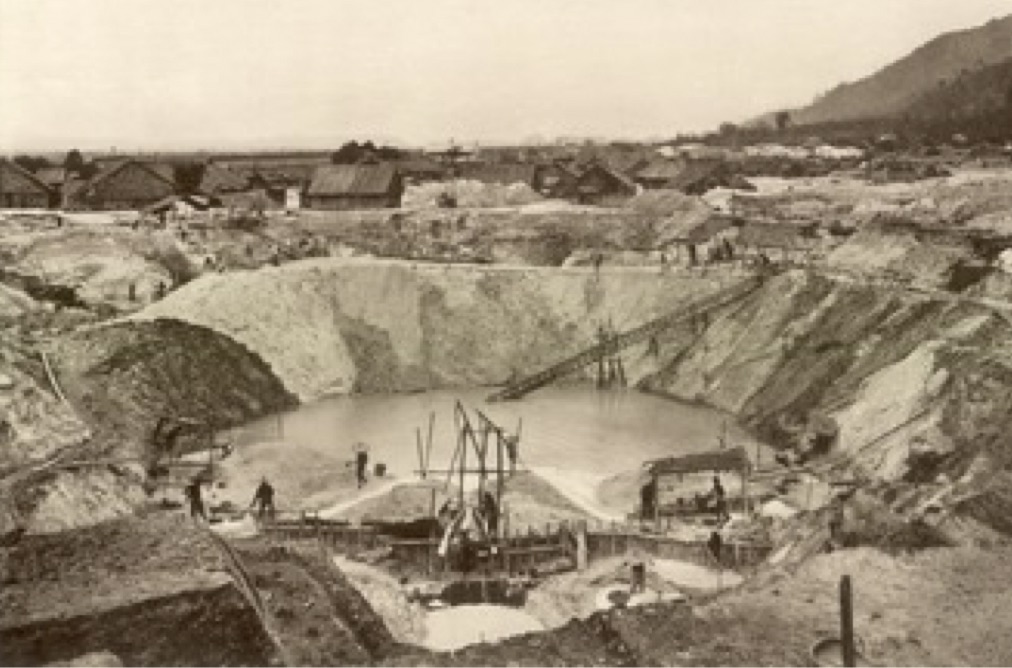

As an island nation, Japan had a very limited amount of natural resources available to use. Malaya, on the other hand, was absolutely brimming with natural resources. At the time, the Malayan Peninsula was estimated to contain the world’s biggest tin mines and about a third of its natural rubber, making it an invaluable prize for the Japanese war machine.

Malaya was so important to Japan’s plans that they launched an invasion on 8 December 1941, a few hours before the more well-known attack on Pearl Harbour.

D-Day of the East

We’ve all heard about the infamous D-Day Landings in Normandy, but did you know that it wasn’t the first big amphibious invasion in modern warfare?

Three years before the Allies stormed the beaches of Normandy, the Japanese enacted their own version of D-Day. One of the key figures behind the invasion force was Major Nakasoni, who determined the best landing sites for an amphibious attack.

Disguised as a commercial traveller, he investigated beaches along the Malayan coastline to measure factors such as water depth, tide patterns and soil stability. Thanks to his efforts, three important sites were identified: Singgora and Pattani in Thailand and Kota Bharu in Kelantan.

On 4 December 1941, the Japanese attack force led by Lieutenant General Tomoyuki Yamashita set sail from Hainan Island. They were spotted by a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) recon plane, which raised alarm bells for the British commanders.

A few days later, another scouting force was shot down by Japanese fighters — the first Allied casualties in the war against Japan.

The invasion began with a bang — literally!

Just after midnight on 8 December 1941, Indian soldiers patrolling the beaches of Kota Bharu noticed dark shapes just off the shoreline — the first sign of Japanese landing crafts. At around 12.30am, the Japanese began bombarding the shoreline. And by 12.45am, the first wave of landing crafts reached the beach.

Within 24 hours, the Japanese had taken over the town of Kota Bharu.

The Invasion of Malaya

While the landing forces were battling in Kota Bharu, the rest of the Japanese army hadn’t been sitting idle.

The invasion of Malaya happened at approximately the same time as attacks on Pearl Harbour, Hong Kong and the Philippines — a devastating surprise attack meant to break the Allies’ will to fight.

Even as the army forces took over Kota Bharu, squadrons of Japanese Zero fighters took to the air. By 4.30am, they had reached their targets: the all-important Royal Air Force (RAF) airfields in Singapore.

With the British air capabilities crippled, the Japanese were able to overrun Malaya within two months. Trapped in Singapore, the remaining British forces held out for as long as they could but were forced to surrender in February 1942.

Less than six months after the original invasion, the Japanese were fully in control of Malaya.

Meet the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss?

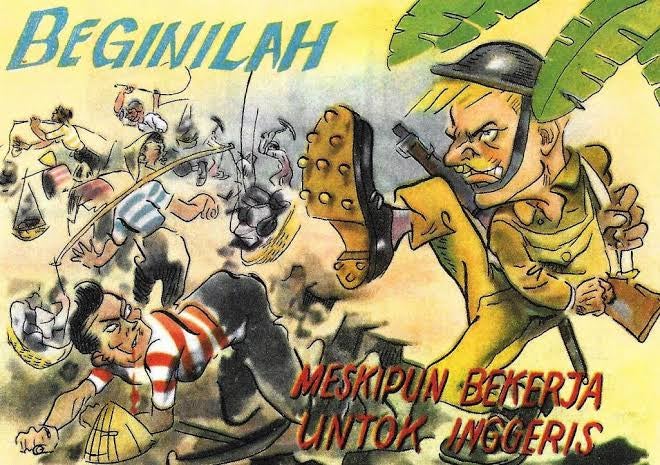

Just like the British before them, the Japanese were interested in Malaya primarily for its resources. Though unlike the British, the Japanese promoted the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere — the idea that they were protecting us from Western colonialism and saving “Asia for the Asiatics”.

Unfortunately, despite their grandiose claims, the truth is when it came to ruling Malaya, the Japanese were even worse than the British. The Japanese colonial policy was based on five main principles:

-

Obtaining materials vital to the war effort

-

Restoration of law and order

-

Self sufficiency of troops in occupied territory

-

Respect for local customs

-

No “hasty” discussion of sovereignty

In other words, they took what they wanted while dangling the prospect of future independence in order to get the local population to cooperate.

However, it was hard for Malayans to trust their message of “cooperate and you’ll be free one day” — especially after the northern states of Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan and Terengganu were given to Thailand as a reward for signing a military alliance.

Japanese-Occupied Malaya was run by the Malay Military Administration (Malai Gunsei Kumbu), a new branch of the Imperial Japanese Army under Chief of General Affairs Department Colonel Watanabe Wataru.

To maintain control, Wataru took advantage of the racial tensions simmering beneath the surface. While the Malays and Indians were given a relatively light touch, he implemented harsh policies against the Chinese population, the most infamous of which was the Sook Ching (“purge through cleansing”).

Sook Ching

In 1942, Masayuki Oishi of the Kempeitai built “screening centres” in Singapore to “test” all Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50. Those who were considered “anti-Japanese” were taken away and executed.

The most infamous of these Sook Ching incidents was the Punggol Point Massacre which occurred on 28 February 1942. Japanese soldiers conducted a door-to-door search, detaining several hundred Chinese locals and transporting them to the “execution grounds” on Punggol Beach.

In one day, between 300 to 400 victims were shot and their bodies either dumped into the sea or simply abandoned where they fell. There are so many bodies on that beach that even 50 years after the clean up, beachgoers have been known to stumble across the occasional skull or remains.

Unlike Singapore, the Chinese population of Malaya was more spread out, making it difficult to “screen” properly. As a result, the Japanese decided to simply massacre any unfortunate Chinese groups that came to their attention.

It is estimated that up to 25,000 Chinese were killed in Johor alone. Entire villages were wiped out, with shell-shocked survivors speaking of mass rapes and sadistic killings of men, women and children alike.

By the end of the occupation, it is believed that approximately 80,000 Chinese had been killed across Singapore and Malaya. As such, it should not come as a surprise that the Chinese were some of the first groups to fight back against the Japanese occupiers.

In his memoirs, former Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew described his own experiences with the Japanese military:

“Genghis Khan and his hordes could not have been more merciless. I have no doubts about whether the two atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were necessary. Without them, hundreds of thousands of civilians in Malaya and Singapore, and millions in Japan itself, would have perished.”

So What Was Life Like For Anyone Who Wasn’t Chinese?

While the Chinese were the most badly affected, everyone living under the Japanese occupation suffered to some extent.

In the beginning, the Indians and Malays were treated with a relatively light hand. The Japanese wanted to gain the support of the Indian community in the hopes of eventually freeing India from British rule, while the Malays were not considered a threat — partially due to the fact that the Malay organisation Kesatuan Melayu Muda had assisted the Japanese during the invasion.

The Kesatuan leaders believed that the Japanese would grant Malaya independence. However, Vice-President Mustapha Hussain was shocked when the Japanese military turned down his requests. Instead, they disbanded his organisation and conscripted his men into a militia.

While the Malayans initially hoped that the Japanese would treat them better than their former British rulers, they were sadly mistaken. Some of the major events of this period included:

The Death Railway

To supply their troops in Burma, the Japanese wanted to build a railroad connecting Thailand and Burma. Officially, it was known as the Thai-Burma Railway. However, those who worked there soon gave it a new nickname: the Death Railway.

Out of the 73,000 Malayans conscripted for this project, around 25,000 would never return home. Known as romusha (the Japanese word for “labourer”), the Malayan workers who initially signed up in the hopes of good wages were horrified to discover working conditions that were similar to a death camp.

Maltreatment, sickness and starvation was rife among the railway workers. There was little food or medication available, and even the tools were lacking.

Forced to do backbreaking work under the watchful eye of their cruel, uncaring guards, thousands of romusha and Prisoners of War (POW) labourers died while constructing the Death Railway.

Banana Money

One of the reasons why so many initially volunteered to work on the Death Railway was due to the fact that the Malayan people were struggling to put food on the table.

After the Japanese invaded, Malaya was cut off from the global economy which had previously made it so rich. With rice imports and other food sources cut off, many Malayan families suffered from hunger and malnutrition.

To make matters worse, the Japanese replaced the Malayan dollar with their own version — known as “banana money” due to their banana tree motif.

One of the big problems with banana money was that it had no serial numbers, making it easy to counterfeit. In addition, some Japanese army units used mobile printing presses to create as much banana money as they wanted, leading to severe hyperinflation.

Although the Japanese tried to force people to accept their banana money, much of the population ended up relying on the black market to survive. By the end of the war, the cost of food in some parts of Malaya and Singapore had shot up to 160 times compared to pre-war levels.

The Resistance

After so much suffering, it should come as no surprise that many Malayans began to fight back against their Japanese oppressors. The most famous of these groups was the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), a paramilitary group founded on 18 December 1941 by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), British colonial government, and other anti-Japanese groups.

Though they could not stand up to the Japanese in open battle, the MPAJA conducted a series of sabotage and ambushes against Japanese forces. As the Japanese began committing more and more atrocities, the MPAJA began attracting more and more Malayans.

By the end of the war, the MPAJA claimed that they had eliminated over 5,500 Japanese troops. However, the Japanese themselves claimed that only 600 of their soldiers had been lost.

The Spirit of Merdeka

On 15 August 1945, the Japanese officially surrendered, marking the end of World War II. However, while the return of the British caused many sighs of relief, many Malayans were now determined to ensure that they would never be invaded again.

Although the Japanese occupation had only lasted for four years, the suffering and hardship it caused had ignited the spirit of independence. Incensed by their poor treatment, many Malayans began to desire the freedom to rule themselves instead of paying fealty to some distant, uncaring ruler across the sea.

For the first time, the cry of “Merdeka” was heard all around the country.

The Struggle for Independence

However, even though the Japanese had been kicked out, the next few years would be far from easy. Shortly after the Japanese left, Communist insurgents began to rise up, leading to the first Emergency which threatened to destroy the fledgling nation of Malaysia before it could even begin.

Yet despite all the difficulties they faced, our ancestors managed to pull through and turn Malaysia into a proud, independent country.

Today, our opponent is not the Japanese nor the British, but a virus. This conflict has overturned our lives and affected each and every single one of us, but as long as we hold true to the spirit of Malaysia, there is no doubt that we shall prevail and come out of this pandemic stronger and more united than ever before.