It was my first week in Kuala Lumpur. My friend took me out in his car, zipping through the weekend traffic in Brickfields.

I exhaled, praising God that the first week had passed. I couch surfed at my friends’ as I haven’t managed to find a flat that fits my budget, that was also accessible by public transport. In 2010, public transport in KL was patchy at best, bus services that were already unreliable compounded by the notorious KL traffic.

I didn’t have a car then. Whilst admiring my friend’s mad skill in negotiating the KL traffic, I was hypnotised by the perpetual inching-forward and abrupt braking. Bored, I looked outside the window, I was immediately attracted to a poster.

“Contract Foreign Domestic Helper” read the headline in bold letters. A silhouette of a female figure in French-styled maid’s uniform was placed in the centre prominently.

“Myanmar, Indonesia, Philippines, Sabah and Sarawak” it continued in a bulleted list.

I read it twice, incredulous, trying to open my very small eyes wider hoping that I had actually misread it the first time.

I had not.

A Jesselton Boy’s Shadow

Growing up in Sabah, I’ve always felt that we’re ever so slightly different from the rest of the Nation; and indeed, some critics said that the differences in priorities are stark.

I had been hearing my parents describe their childhood when North Borneo was still a British Crown Colony. How it was a classier and idyllic time.

My family is like a little snapshot of the Sabahan demography. Both my parents are of Sabahan Native and Chinese mixed parentage.

More often than not, when a West Malaysian discovered that I’m a Sabahan Native, they are only interested in what kind of discount I can get when purchasing property. When I explained about my heritage, I would usually get a dismissive “Don’t worry, you look exactly like a Chinese person”. Perhaps in a ‘positively’ racist way, if that’s even a thing, since when did looking less like a Chinese become something that I should worry about?

There has always been a little Britishness in my parents. Most notably their pseudo-British accent with a thick Sabahan undertone. Small talks between my mother and our neighbour Aunty Yun were constantly about the weather. I was fed beans on toast for breakfast, Worcester sauce in stir-frys, and Oxford sauce on almost anything.

I was mainly brought up as a Malaysian Chinese, the difference is the Hakka Chinese dialect we spoke at home was heavily sandwiched with Sabahan Malay creole or Bahasa Sabah and a bucket-load of Kadazan vocabularies.

I can’t speak Kadazan myself. I could count in Kadazan from one to 10, wish you a good day and get myself in real trouble; but not nearly enough to carry a proper conversation. Even so, my Malay is so accented, that it’s still detectable until today. But I’m proud of that, because that’s a part of my identity that I get to preserve, much like a historical feature on a listed building.

What struck me at first was how noticeable my accent was to Peninsular Malaysians. Nobody made fun of it, but it would always be pointed out in most endearing ways.

I was once called a “contract”, by an acquaintance, who must have thought that it was an okay joke. What could that have meant? I could fill in the blank with so many possible suffixes – was I victimizing myself for interpreting that as a slur?

Despite having been bothered by the name-calling, I did not confront him, being a mild-mannered Sabahan then.

To me, that was a slap in the face for all capable, hardworking Bornean Malaysians who earn an honest living;

That remark discounted our efforts in overcoming a stereotype that exists for decades.

Perhaps that has been one of the reasons why I consciously neutralise my accent when I’m speaking with someone from a different culture.

Looking Back at the History

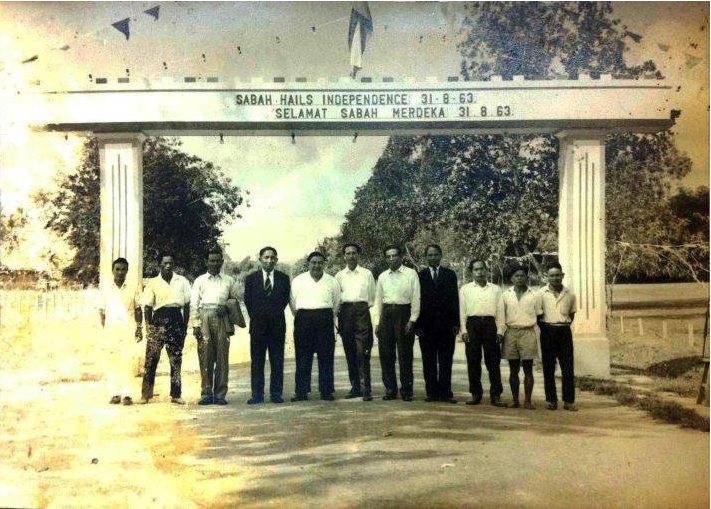

On 31 August 1963, North Borneo attained self-government. The Cobbold Commission was set up in 1962 to determine whether the people of Sabah and Sarawak favoured the proposed union of the Federation of Malaysia, and found that the union was generally favoured by the people.

Most ethnic community leaders of Sabah, namely, Mustapha Harun representing the native Muslims, Donald Stephens representing the non-Muslim natives and Khoo Siak Chew representing the Chinese, would eventually support the union. After discussion culminating in the Malaysia Agreement (MA63) and 20-point agreement, on 16 September 1963 North Borneo (as Sabah) was united with Malaya, Sarawak and Singapore, to form the independent Federation of Malaysia.

MA63 recognised Sabah and Sarawak’s status as equal partners to then-Malaya and Singapore, which formed the constituent units of Malaysia. However, in 1976, a controversial amendment was passed in Parliament that shifted the status of Sabah and Sarawak to under the Malaysian federation, together with the states in Peninsular Malaysia.

This change in status, coupled with other issues like the exploitation of natural resources and the lack of support from the federal government, has contributed to grievances felt by certain quarters in Sabah and Sarawak.

Most Sabahans who have lived through the 70s, well, those who I know of, were mainly gutted by a foiled separatist movement then. Growing up surrounded by adults who had perpetually-simmering dissatisfaction against the federal government, I too, developed a seperatist world view, and a Sabahan nationalist who essentially felt that the Federation owes us everything, and the whole Nation should apologise for the predicament we were in.

Sabah, since joining the federation, has been one of the poorest states in Malaysia, and we have the lowest Human Development Index (HDI). My parents would tell me the Federal took all of the oil money and we were left with peanuts.

Sabah and Sarawak contribute roughly 60 percent of Malaysia’s total petroleum output. However, each state government received a mere 5 percent of the oil royalties.

A Sabahan Boy’s Struggle

I did my internship at a five-star international hotel located in the Kota Kinabalu CBD. I would have to park my car a 10-minute walk away at an open carpark, as the street parking would cost me RM30 per day; which was astronomical for an unpaid placement.

Fortunately, lunch was provided for all employees, not too bad if you could see past the complete lack in variety.

Once a week, my workmate and I would treat ourselves to a meal of Malay mixed rice at the foodcourt of a shopping mall next door, that could cost at least RM15 a pop; a real luxury for someone who made zero ringgit in a relatively expensive city.

One of the causes that the hotel supported was a home for rural children. The hotel’s patronage towards this home has effectively been keeping these children in schools by housing them for three months at a time, before they trek the 35km winding trail across mountains and rivers to return home; which really paints a picture of the state of infrastructure development in Sabah.

On 4 April 2019, a bill proposing an amendment to the Constitution of Malaysia was tabled in the Dewan Rakyat of the Parliament of Malaysia. The bill proposes to amend Article 1(2) so as to restore the status of the two East Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak according to the original content of the Malaysia Agreement that was signed in 1963. Despite six hours of debate in the Parliament during the second reading of the bill on 9 April, only 138 MPs supported the bill, 10 votes short of the two-thirds majority of the chamber, 148 votes, required for amendments to the Constitution. The remaining 59 (non-absent) votes were abstentions, all of which are from opposition parties.

The outcome of the motion was one that in a way, undermined the desire of most Sabahans, for a fairer treatment from being part of the federation.

The True Meaning of Merdeka

So what does merdeka mean anyway? Is it freedom? And what about self identity? Perhaps it’s time that we move on and look into the future and be truly free from the notion of differences.

How, you ask?

Spot the similarity and not the differences – it is far too easy to point out the fact that someone is different from you; worse if you judged them. Try to find things in common, it makes a good conversation starter.

Know the basic geography of East Malaysia – confusing the capitals of the Bornean Malaysian states are not exactly a deadly sin, but it makes you sound incredibly ignorant. I once had a colleague who believed me when I told him that I took a speedboat back to Sabah.

And Sabahans, be proud of who you are – you may codeswitch your accents every now and again so our West Malaysian siblings can understand us better, but don’t ever lose your identity.

You see, we celebrate Merdeka not because we think that there is a practical way to “break free” from the federation, but it is important for us to remember that we crossed an important milestone in our historical identity. To know where we come from, and in doing so, being able to appreciate what we mutually benefit from – a stable, peaceful and united Malaysia.

While we celebrate the spirit of patriotism and the unity of Malaysians far and wide, let us not forget our Asli brothers and sisters, a society known for their resilience in weathering whatever storms may come their way.