Content warning: This article will challenge preconceived notions of masculinity. Also includes discussion of male health and innuendo.

Let me tell you two stories with a common theme.

– – –

The first story is of a man in his 20s, fresh out of the first MCO. Deciding to brave the wilderness of Taman Botani in Shah Alam, he walks through 10km of road – the longest he’s walked in a while.

Days later, he experiences pain in his nether regions. Sometimes nausea. The chronic pain of being kicked in between the legs. He decides to wait it out, see if it gets better.

But morbid curiosity gets the better of him. He starts looking at his symptoms, searching high and low on Google for answers to why the pain won’t go away. The results aren’t encouraging: testicular torsion, testicular cancer and the like.

He mentions his plight to a colleague in passing at work, who tells him to get it checked out urgently.

Peer pressure works wonders on the millennial mind. Swallowing his pride, he goes to a doctor to get checked below the belt. The doctor finds nothing – no lumps, no bruising – then asks if he’s done any strenuous exercise.

Turns out, an overstretched tendon was the cause. After some rest, the pain goes away and all is well. The man in his 20s breathes a sigh of relief.

– – –

The next story is of a retiree in his 60s, a government pensioner who started to pick up running again and reignite an old pastime. After building stamina and confidence through a few runs, he joins a running group and goes to Penang for a marathon in 2016.

Past the 26th kilometre, the retiree knows something is wrong. He breaks out in cold sweat, his vision blurs, his breathing becomes laboured. There’s a tightness in his chest.

He pauses, trying to catch his breath. Maybe it’s fatigue. After all, he didn’t sleep well the night before since he was so excited about the marathon. He waits.

A minute passes. Two minutes. Five. The cornucopia of sensations seems to fade ever so slightly. He continues with the marathon and completes it, but with a blemish on his speed record.

Months pass and the retiree lives life as usual. Hitting the gym, running, and spending time with his friends. But his performance suffers – his speed isn’t what it used to be and he gets cramps every run.

Then one day as he’s running in his local field, he collapses, injuring his head. His family is notified and he is rushed to the hospital. He resists, but at the behest of his two sons, he gets checked.

The doctors find heart palpitations, signs of heart damage. Using his pensioner benefits, he checks into the National Heart Institute (IJN), where it’s determined that he needs a quadruple bypass.

Complications mount – his water intake is not restricted and it enters his lungs, nearly killing him. He is admitted into intensive care, where he nearly passes away from the complications.

But ultimately, he survives. The retiree is discharged from IJN and begins his long road to recovery. In 2020, he walks daily, exercising to nurse his damaged heart.

– – –

Confession time. The first man? He’s me. The retiree is my father.

The Absolute State of Men’s Health

Pithy anecdotes aside, these life stories call our differing attitudes towards our health into question: why was my father not willing to get examined for a heart issue while I was more accepting of having a medical professional handle my privates?

Maybe it’s because I’ve not been one to identify as a “dude-bro”, alpha male, or very masculine. Also, I’ve kept abreast of gender issues and, as a mild hypochondriac, read up on health problems to scare myself to sleep. But even despite all that, I still maintained a “wait and see” mentality until my colleague convinced me otherwise.

It’s a stalwart of traditional masculinity that I learned from my father, the school of thought that introduced maxims like “tough it out”, “don’t be a wimp”, “crying is unmanly”. The words of toxic masculinity.

We’re not alone in believing these sayings. Men across the globe subscribe to attributes like independence, risk-taking, a sense of invulnerability, and a required tolerance of pain.

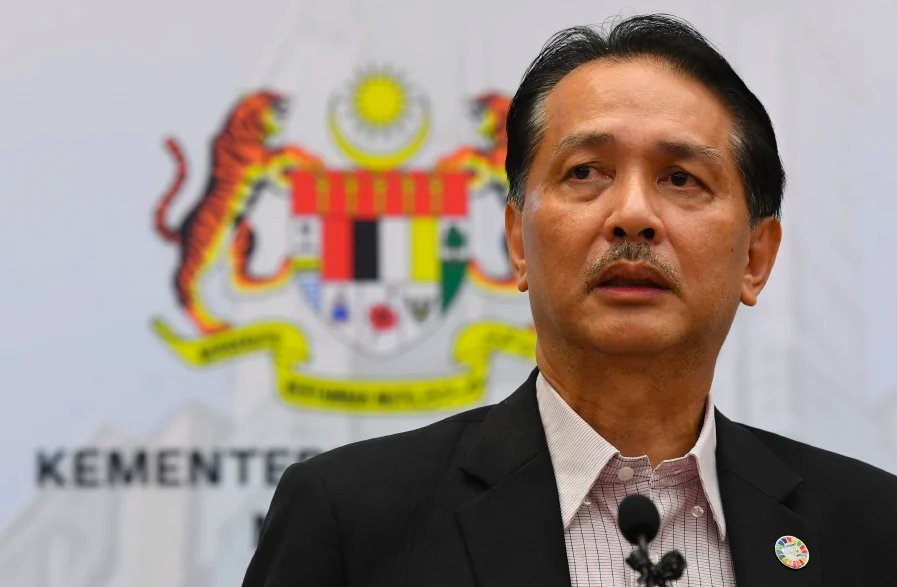

These attributes, according to Health Director-General YBhg. Datuk Dr Noor Hisham bin Abdullah, increase men’s exposure to disease risk factors like hypertension, diabetes and smoking.

Here are the facts.

The Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) estimates that men live an average of five years shorter than women (72 vs 77 years). Supplementing that, the Malaysian Burden of Disease study of 2008 showed that the total years of life lost (YLL) that year was 1.51 million, in which 0.92 million (60.7%) were among males.

Now for the cherry on top of the bad news cake: despite these statistics, males have a lower tendency to get health screenings – only 4.7% of men vs 5.8% of women in 2018.

The numbers don’t paint a pretty picture. I can safely say that I am part of that small percentage, but what of my father and men like him who don’t want to get checked or don’t know better?

I Hope You’ve Got Some Good News, Bro.

While the outlook is grim, there is hope – we can find solace in the knowledge that men’s health has been scrutinised for a while now.

In 2016, the Malaysian Ministry of Health introduced the National Men’s Health Action Plan 2018-2023. At the time, it was one of four in the world, according to the then-Health Minister Datuk Seri Dr. S. Subramaniam.

It aims to extend male life expectancy, promote men’s responsibility and participation in sexual health, and empower them with opportunities to improve their health. The Plan also outlines the Ministry’s strategy, involving accessibility improvements, better education, promotion of men’s health campaigns and legislature changes to name a few.

The discourse around men’s health is also seeing change, albeit slowly. Malaysia is starting to open up to the idea that this is a topic that should be talked about. Recently, CIMB Bank Chairman Datuk Seri Nazir Razak opened up about his battle with prostate cancer to boost awareness about the disease.

This is happening alongside the freedom to express emotion and breaking preconceived notions of masculinity, both also key talking points of male well-being.

They are topics that will be talked about in the Men’s Health World Congress, an event that sees men’s health professionals across the globe gathering to discuss key topics like gender perspective in health and social policy, high-risk behaviour, and male mental health.

In 2021, it will be held on our shores – Kuching to be exact. From 7-9 October 2021, top minds will gather at the Borneo Convention Centre for the Congress, jointly organised by the Malaysian Society of Andrology and the Study of Ageing Males (MSASAM) and the Malaysian Clearinghouse for Men’s Health.

While it’s not open to the layperson, it will be worth keeping an eye on to see where Malaysia’s stance on men’s health goes from there. I, for one, will be watching with great interest.

In the Meantime…

While the experts look for a better way, we men must do what we can with the resources we have. All it takes is a bit of “get over yourself” and a little (admittedly toxic) “suck it up”.

Harsh words, but let me explain.

-

Get over yourself = Accept that you’re human and need help

Remember that sense of invulnerability I mentioned earlier? Time to let it go, man.

You’re not Superman; you’re more like Batman – despite how strong he is, he still needs Alfred (did you know he’s also an experienced physician?).

Writing from personal experience, if you feel something is wrong, the worst thing you could do is leave it be. If my father had his heart checked out before he fainted, his heart damage may not have been so severe.

Sure, ignorance might comfort you, but what if it’s serious? Reevaluate the risks.

-

Suck it up = Brave discomfort for your well-being

Some men may not be comfortable with the whole idea of getting examined.

Yes, it can be embarrassing, having someone that’s not yourself or a significant other touching your body (especially your penis and scrotum). I certainly felt that way when I was reading up the procedure for a testicular cancer examination.

But again, early detection of any possible issue outweighs the shame you might feel, so bite the bullet and get it done. You might just save your life.

And personally, the nitrile gloves my doctor used added a degree of separation, so it wasn’t too bad.

As we look after ourselves now, take heart that it will be better – the path is being paved towards a better future for Malaysian men. We can look forward to the day when stigma towards men’s health is a thing of the past.

To when we no longer have to suffer in silence. To a healthier future for Malaysian men.

For now, we can broaden our focus beyond just physical health and look towards greater male well-being. Starting with toxic masculinity.