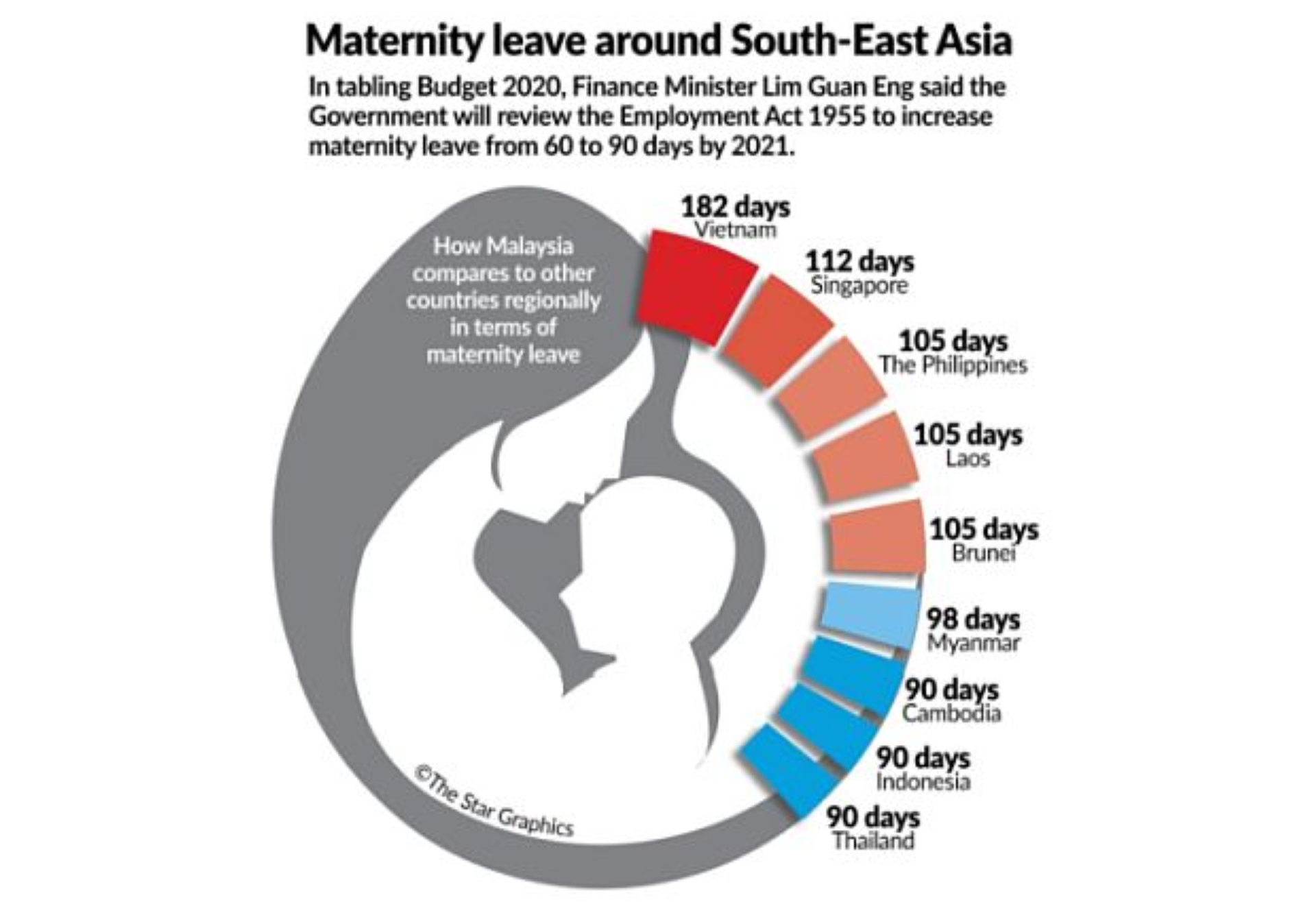

The local media scene was recently embroiled in a debate concerning the appropriate amount of maternity leave given to new mothers. The topic of how long is too long of a rest after one pops a baby isn’t a foreign one, as our government has been supporting the idea of implementing a 90-day maternity leave for the private sector.

Just to provide some context, the Malaysian public workforce allocates mandatory 90 days of maternity leave and seven days of paternity leave. The standards according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) provides 98 days.

The argument resurfaced yet again when it was announced during the Budget 2020 speech. Naturally, it sparked opinions from both sides – the parents and the employers. For any new parent, the extended maternity leave is a godsend but the implications on businesses raised some fair points too.

For big corporations, absorbing the cost wouldn’t be too much of a hassle, but the issue is not so easily solved among SMEs. At the moment, 98% out of one million registered and active employers nationwide are SMEs and about 650,000 of them consist of micro businesses with fewer than five employees. And if one woman is down for three months, it would presumably affect the intricacies of the business quite negatively.

Should the cost be absorbed by the government or be included in social security coverage is a discussion for another day. Right now, the imminent fact is that a longer period of maternity leave is the right move to improve the dynamics of our Malaysian workforce in the long run.

The benefits in terms of biology and psychology are aplenty, but here’s what would happen if the maternity leave is cut short or doesn’t increase further in the future:

Productivity Decreases in the Long Run

On the surface, it may seem like a longer maternity leave will cause the organisation’s productivity to drop but the belief is actually quite the contrary.

Malaysian Trade Union Congress (MTUC) secretary-general J. Solomon was quoted saying that employers found out that a longer maternity leave actively contributes to an increase in productivity which simultaneously reduces pressure in the workplace.

Meanwhile, The Centre for Economic Policy Research Malaysia (CEPR) echoes the above statement with real, hard data. Their study revealed that 89% of their respondents reported positive impact or an indifference on productivity after returning to work. A more significant discovery would be the fact that contribution rate increased to 93% and a whopping 99% for morale.

One may wonder how does taking a longer break equate to a rise in productivity when the amount of working days technically decreases?

We’re no experts on the birthing subject, but it is practically general knowledge that a new mother would undergo and adjust to a range of major emotional and physical transitions which include time to heal, added responsibilities, change in schedules and more.

In addition to everything that needs to be done with a new human being, the parents will also have another task of securing a suitable and trusted caregiver when they return to work. This requires time for all involved parties to adjust and become accustomed to one another.

If all these processes are forced to be rushed, it may lead the parents to become more distracted, anxious and jaded when they return to their job as their recovery time is insufficient.

At the end of the day, supportive employers produce happier and more committed workers, and better productivity is the measurable after-effect.

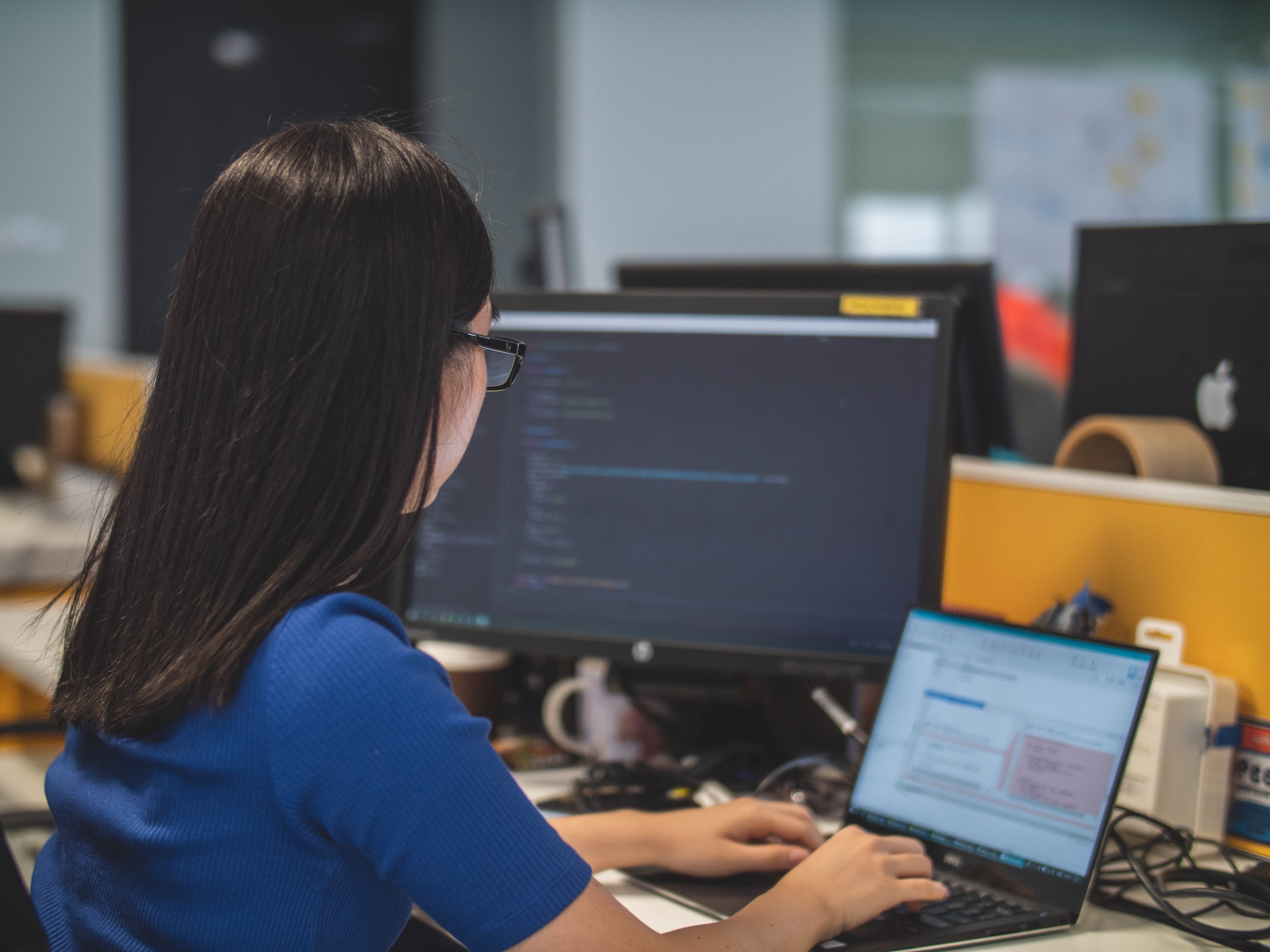

Less Women in the Workforce

With direct correlation to the point above, there will be less women in the workforce if our country doesn’t make the move to start implementing the 90 days maternity leave as the difficulty in balancing both motherhood and work will cause employers to gradually lose female talents.

In fact, did you know that women’s labour force participation in Malaysia is one of the lowest in South East Asia at 55.8%, as compared to 80.9% for men?

Providing more employee benefits for mothers will not only attract and retain working parents, but can fill in the gap of a more family-friendly working culture that many nations, even developed ones, are struggling with.

The root cause here is that working mothers are in an arduous position of being torn between motherhood and their career. More often than not, dual income is the most ideal, or even necessary in some households to sustain a comfortable lifestyle.

But for mothers who can afford to leave the workforce, they would rather bear a tighter cost of childcare than grapple with new challenges faced at work in light of motherhood.

These challenges can be avoided if employers start viewing maternity leave as a brief interlude in a woman’s career rather than something that halts their professional advancement permanently.

A research done by DCU Business School found that organisations who demonstrated their beliefs on maternity leave being just a temporary respite are more successful in retaining high-potential female employees. These women are also more motivated and focused with enriched professional relationships post-maternity leave.

To support mothers in continuing their careers will ultimately go beyond extending maternity leave. It involves analysing individual scenarios and then amending policies and structure, which may include more flexibility at work, parental benefits, financial packages and the likes.

After all, the common ground is that women would want to feel valued, supported and empowered to stay in their career without having to bear the brunt of prejudicial judgment that comes with their new title of being a mother.

The Beginning of an Ageing Nation

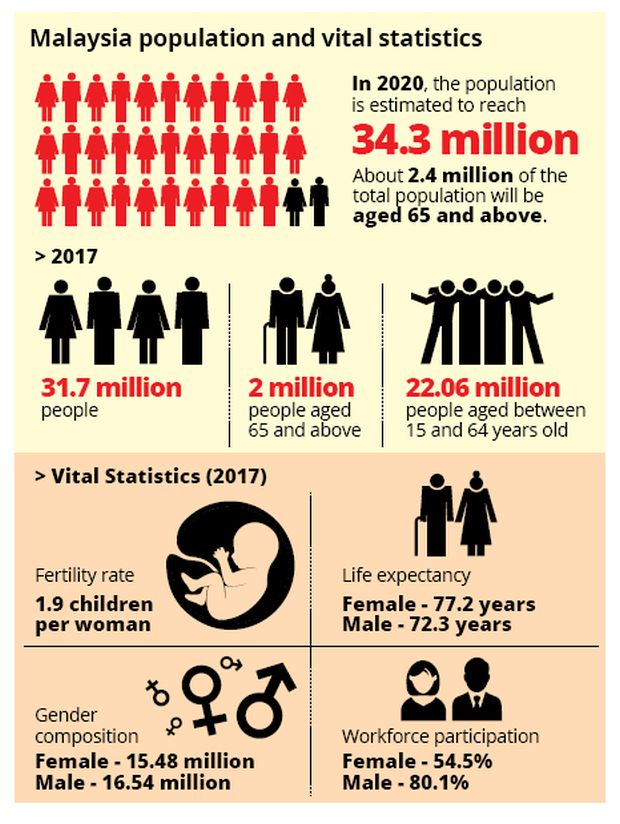

With the rising cost of living, a single income family is simply disfavoured to provide their children with an ideal quality of life. And if the maternity leave policy remains unchanged, the fertility rate will consequently dwindle.

Unexpectedly, this contributes to Malaysia turning into an ageing nation and the problem might arrive sooner than we think. Frankly speaking, we are already on the way to becoming an ageing population by 2020.

Based on the metrics provided by World Health Organisation (WHO), a country is at risk of being labelled as an “ageing nation” when 7% of the total population is aged 65 and above.

To bring it closer to home, findings by Universiti Malaya’s Social Wellbeing Research Centre estimated that the number of Malaysians reaching the age of 60 and above will hit 3.5 million in 2020 and 6.3 million in 2040. These figures accumulate to around 20% of our total population so yes, we are more than qualified to be an ageing nation.

And what does that mean for the growth of our country?

Basically, our economy would be affected by productivity, labour participation and saving rates. This may cause a significant financial burden on the government’s fiscal position as public expenditure would increase from a large surge of pension support.

A report by the Economic Outlook 2019 announced that to manage the negative consequences of an ageing population, a crucial fix would be for more women to contribute to the workforce. And this goes back to rectifying two issues at hand without sacrificing one or the other – for families to improve their fertility rate and for mothers to continue working. And that will only be enabled through a maternity policy that encompasses a realistic resolution for family planning to happen.

Do you agree with our thoughts? Read more Malaysian perspectives here and get daily updates from our Facebook and Instagram.