For many of us in the younger generations (and yes, I’m in my 20s, so I still count as young), the events of 13 May can feel a bit like ancient history. Interesting, inspiring yet ultimately unimportant to our everyday lives.

After all, those events happened decades before we were born. Heck, they could have happened even before our parents had been born!

However, while it is true that the riots themselves were just a single incident in the grand scheme of things, the effects of 13 May still linger with us even to this day.

Our History of Racism

If you’d asked any Malaysian today to list our country’s biggest problems, odds are that “racism” is going to be one of the first responses.

The shadow of racism between Chinese, Malays, Indians and every other race and religion has cast a pall on Malaysian lives for as long as any of us can remember.

While the 13 May riots is one of the biggest examples of racism rearing its ugly head, racism is a problem that’s been in this country from the colonial era up till today.

So how did it all begin?

To answer this question, we need to go all the way back to the British Colonial era.

The Roots of Racism

In hindsight, the British can ultimately be considered responsible for many of the problems that still exist in our society today.

Unlike many of the other European colonial empires, the British saw their colonies as an economic investment. They weren’t interested in “civilising” the Malays or converting the locals to a more Westernised religion or culture.

For the British, the number one priority was always about making profits.

Even back then, Malaya was known as a land that was blessed with vast natural resources. During this period, the British invested heavily in Malaysian industry and agriculture, transforming it into a world leader in rubber and tin.

However, extracting these valuable resources required a large and skilled labour force. The problem was that the British did not think the local Malays were good workers. Part of it was plain racism — Malays were seen as friendly, but somewhat lazy and unreliable.

On a more practical level, there were simply too few of them to do all the jobs that the British wanted. The British plans required massive amounts of cheap labour and most of the Malays were already working in other sectors (farming, fishing, etc.).

To solve this problem, the British government opened the borders and brought in thousands of Chinese and Indian immigrants.

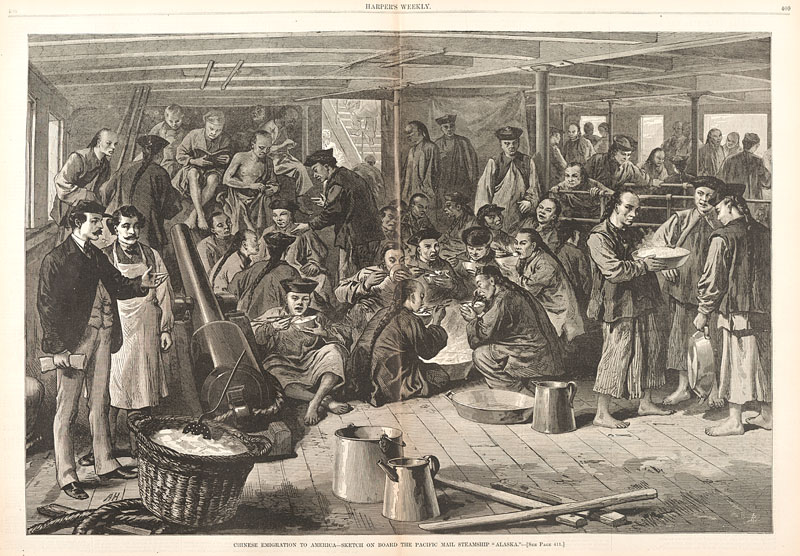

The Great Migration

Between 1800 and 1941, millions of Chinese and Indians moved to Malaya to work as labourers, miners, planters and merchants, bringing along their cultures, languages and beliefs.

This period was a time of great opportunity as well as upheaval. In order to survive, each of the three main races were forced to adapt and change in ways that no one could have predicted.

The Chinese Immigration

Many of the original Chinese immigrants were farmers and labourers from rural China, who were attracted by all the relatively well-paying jobs available in Malaya.

Many of them weren’t actually interested in living here long term. Instead, they saved up so that they could return to their families in China after making their fortune. However, over the years more and more Chinese ended up staying.

By 1891, a census found that the states of Perak and Selangor had become Chinese majority states.

As more and more tin mines opened, the Chinese immigrants thrived. They created many mining communities, each run by a Kapitan Cina — a Chinese official who was basically the equivalent of a town mayor.

These Kapitan Cina acted as middle management, bridging the gap between the ordinary citizens and their colonial overlords. As Malaya became more developed, many of them gained a great deal of power — Yap Ah Loy, the Kapitan Cina of Kuala Lumpur, was considered the richest man in Malaya back in the 1890s.

The Indian Immigration

Just like the Chinese, millions of Indians moved to British Malaya in search of work. The majority of them were ethnically Tamil, with smaller communities of Telugus, Malayalis, Sikhs and other northern Indian groups.

Unlike the Chinese, however, many Indian immigrants struggled to improve their lives.

Part of the problem was that the Indian community was split between Hindus and Muslims, many of whom refused to cooperate with those of the ‘wrong’ religion.

They were also divided due to their traditional caste system — the higher caste Indians eventually evolved into an elite educated class, while the lower caste remained stuck as poor and uneducated labourers.

This class stratification issue can be seen among Malaysia’s Indian population to this day. The upper-class Indians are among the richest and most successful groups in our society, but a substantial number of Malaysian Indians remain as poor as ever.

The Malays and Immigration

As more and more foreigners moved in, the local Malays began to grow alarmed. Although their standards of living had improved, many of them feared that they were soon about to become a minority in their own country. The Sultans, who were seen as British collaborators, lost much of their traditional prestige.

Instead, many Malays turned towards religion. The British control was weaker in the Unfederated Malay States (Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis and Terengganu), which allowed them to become strongholds of Islamic conservatism — a legacy that remains to this day.

In the Federated Malay States, however, more Malays gained a western education. Here, the Malays turned to politics rather than religion in order to secure their place.

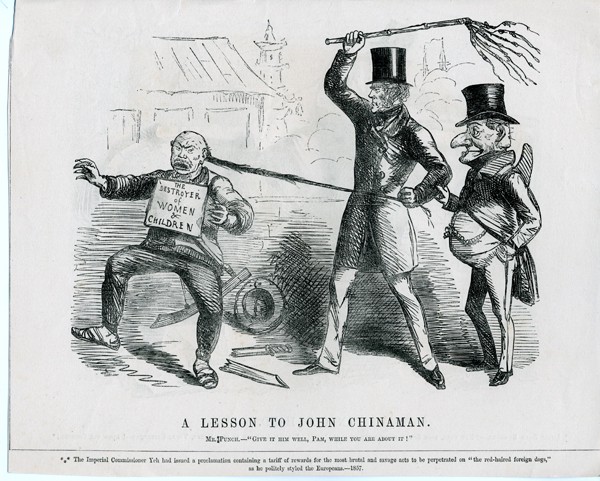

The Perfidious British

As the ones who brought in the Chinese and Indian workers in the first place, the British are regarded as the root cause of racism in Malaysia. More specifically, modern Malaysian racism can be linked to the lack of assimilation between the Malays and non-Malays during this era.

When it came to their colonies, the British favoured a “divide and conquer” style of practice.

In order to keep the locals from uniting against them, they would try to keep everyone isolated and distrustful of each other — after all, if they were all busy fighting each other, they wouldn’t have the energy to try fighting against the British rulers.

Simply put, the British kept each group separate; the Malays lived in villages, the Chinese in towns and the Indians on plantations. Each group lived in their own neighbourhoods surrounded by other members of their own group. They all had their own religions, languages, schools, etc., which made them more suspicious and less welcoming to anyone outside of their group.

To make matters worse, the official policy of the British was that Malaya belonged to the Malays and that all the other races were “guest workers” — a concept that certain groups have carried to this day (does the word “pendatang” ring any bells?).

As a result, Malays received the lion’s share of government aid and were prioritised when it came to government jobs. This led to increasing tension with each new generation of Malayan-born Chinese and Indians, many of whom were upset that they were being discriminated against just because they were born of a different race.

The Invasion of Malaya

The Japanese Occupation of Malaya played a critical role in our country’s history. In fact, many of the events that led to Merdeka had their origins in this time period. Unfortunately, this time period is also when the seeds of Malaysian racism began to bloom for the first time.

Just like the British, the Japanese used “divide and conquer” in order to maintain control of Malaya. However, unlike the British, the Japanese were far more active when it came to turning one ethnic group against another.

During the invasion, organisations like Kesatuan Melaya Muda (KMM), actively aided the Japanese in order to overthrow their colonial rulers. As one of the first groups to focus on the concept of ketuanan Melayu, KKM hoped that the Japanese would help them establish a true Malay state where they would be on top.

However, while they seemed to favour the Malays on the surface, the Japanese also had no intention of keeping their promises. When KKM founder Ibrahim bin Yaacob made a formal request for Malayan independence, the Japanese (presumably after laughing in his face) promptly disbanded the KKM and converted them into a militia group instead.

But while the Malays dealt with betrayal, the Chinese were actively being oppressed through a practice known as Sook Ching (“purge through cleansing”).

Chinese businesses were taken over, their schools were burned down, and their families hunted down and executed as “undesirables”. By the end of the occupation, it is estimated that around 80,000 Chinese civilians living across Malaya and Singapore had been massacred.

Though they were often overlooked, Malaya’s Indian community also suffered greatly during this time. While they were not as actively targeted as the Chinese, thousands of Indian workers were moved from Malaya to Thailand and Myanmar, where they were forced to do hard labour in horrific conditions under the watchful eye of cruel Japanese overseers.

In his book “The Railway Man: A POW’s Searing Account of War, Brutality and Forgiveness“, Eric Lomax recorded some of the cruelties experienced by the Indian workers in their labour camps:

“The Japanese sent in a huge labour force of Tamils, who were as usual treated as atomized slaves, starved and brutalized and dying in handfuls every week. Cholera broke out in the Tamil camp, and the Japanese railway administration found a novel way of containing the epidemic: they shot its victims.”

The Resistance

Although the Malays had experienced a noticeable drop in their standard of living, their community had never been actively targeted or mistreated. In fact, the Japanese fanned the flames of Malay nationalism by actively spreading anti-Chinese propaganda and sending Malay soldiers to fight Chinese resistance groups.

To survive Sook Ching, thousands of young Chinese fled the cities. Most of them ended up joining various resistance groups such as the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). Though they suffered from heavy losses, the cruelties of the Japanese soldiers ensured that there was never a shortage of recruits.

As Malay soldiers and Chinese resistance fighters clashed, each group grew to hate each other with a burning fervour. To the Malays, the Chinese were criminals and vagrants standing in the way of a new Malaya for the Malays. To the Chinese, the Malays were traitors who had happily helped the Japanese massacre their friends and families.

The Rocky Road to Independence

The Japanese Occupation only lasted from 1942 to 1945. But the events of those three years had a significant effect on everyone living in Malaya. Without the Japanese to distract them, the slowly simmering racist sentiments brewing across Malaya came to a boil.

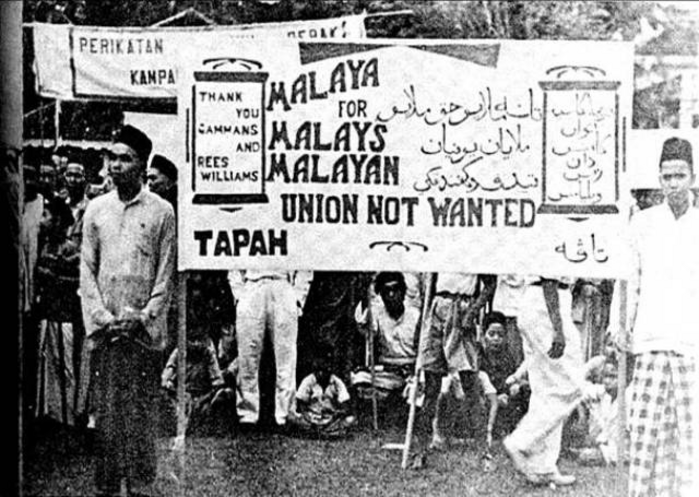

After the British returned, they set up new plans for a Malayan Union, combining Penang, Malacca, and all the Federated and Unfederated Malay States into a single Crown Colony which would eventually be given independence.

However, the Malays were strongly against this plan. Not only would it weaken the Sultans’ positions, but it would also grant citizenship to the ethnic Chinese and Indians — who the British saw as more loyal since they actively resisted the occupation while several Malay groups collaborated with the Japanese.

In response to the Malayan Union, the Chief Minister of Johor Dato’ Sir Onn bin Dato’ Jaafar founded the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) in 1946. UMNO’s followers wanted independence for Malaya, but demanded that the new state was run exclusively by Malays only.

The Resistance Round 2: Now With Extra Communism

In the end, UMNO got their wish. The British replaced the Malayan Union with the Federation of Malaya, which restored the Malay Sultans to their former positions.

Unfortunately, for UMNO, while the MPAJA was disbanded after the Japanese surrender, most of their resistance fighters were still around. Many of them had joined the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), which called for immediate independence and full equality for all races.

One of these MPAJA veterans was a man named Chin Peng who took control of the MCP in March 1947. Frustrated by the Federation of Malaya (which he saw as undemocratic and biased towards the Malay elites) and alarmed by the outlawing of local trade unions, he turned MCP away from its formerly peaceful strategies in favour of a more direct response.

Under his leadership, the MCP became increasingly violent, culminating in the murder of three European plantation managers who had been accused of being harsh and cruel towards their workers.

Regardless of whether or not they were justified, these murders were the straw that broke the camel’s back. The British banned the MCP, arresting hundreds of its militants.

Chin Peng became a wanted man with a reward of $250,000 for his head, but somehow escaped arrest and fled into the jungles with around 13,000 former MPAJA fighters who soon rebranded themselves as the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA).

The Emergency

Alarmed by this insurgent army, the colonial government declared Malaysia’s very first state of emergency, which lasted from 1948 to 1960.

The existence of a Chinese-majority communist army hiding in our jungles had a significant impact on race relations. While the MPLA originally enjoyed support from the ordinary Chinese rakyat, they quickly found out that without an enemy as evil as the Japanese, people were a lot less interested in violence and terrorism.

In 1951, Communist fighters assassinated the British High Commissioner Sir Henry Gurney, gunning him down while on his way to a resort near Fraser’s Hill. However, such terrorist tactics backfired dramatically, as even many of the moderate Chinese disapproved of such actions.

By 1954, the Emergency was more or less over. The majority of MPLA fighters had given up, and though Chin Peng and a diehard group of supporters continued to cause problems from hidden bases in the dense jungles along the Thai border for many years, their plans for a glorious revolution had failed.

However, many of the moderate Chinese would find more success as part of the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), which aimed to work with UMNO and negotiate a policy of equal citizenship without resorting to violence.

Establishing Malaysia

Throughout the 50s, UMNO, MCA and the British government worked together to set up a constitution that would provide equal citizenship for all races. In exchange, MCA agreed to several concessions, including:

-

Malay as the official language

-

Subsidising Malay education and economic development

-

Establishing the position of Yang di-Pertuan Agong

In a way, this allowed UMNO to get what they wanted — a Malaya run by the Malays. Even to this day, Malays continue to hold a majority of positions in the civil service, the army and the police.

However, while most people were relieved to see the British go, these compromises were only papering over the racial tensions that were brimming just under the surface.

The Lead Up to May 13

12 years after achieving independence, the tension between the Malays and the Chinese would come to a head.

Even before Merdeka, there had been many heated debates between Malay supremacists, who wanted to establish Ketuanan Melayu and Chinese groups, who were keen on protecting their own racial interests. Caught in between were the other non-Malay opposition groups, who argued for everyone to integrate and become a real “Malaysian Malaysia“.

Unfortunately for the latter, one of the big issues faced by the newly-independent Malaysia was the stark division of wealth between the Chinese (who lived in more urban areas and were believed to control the country’s economy) and the Malays (who tended to be poorer and more rural, but were granted special privileges under the constitution).

This tension led to several incidences of racial violence, including a riot in George Town that resulted in days of violence and several deaths.

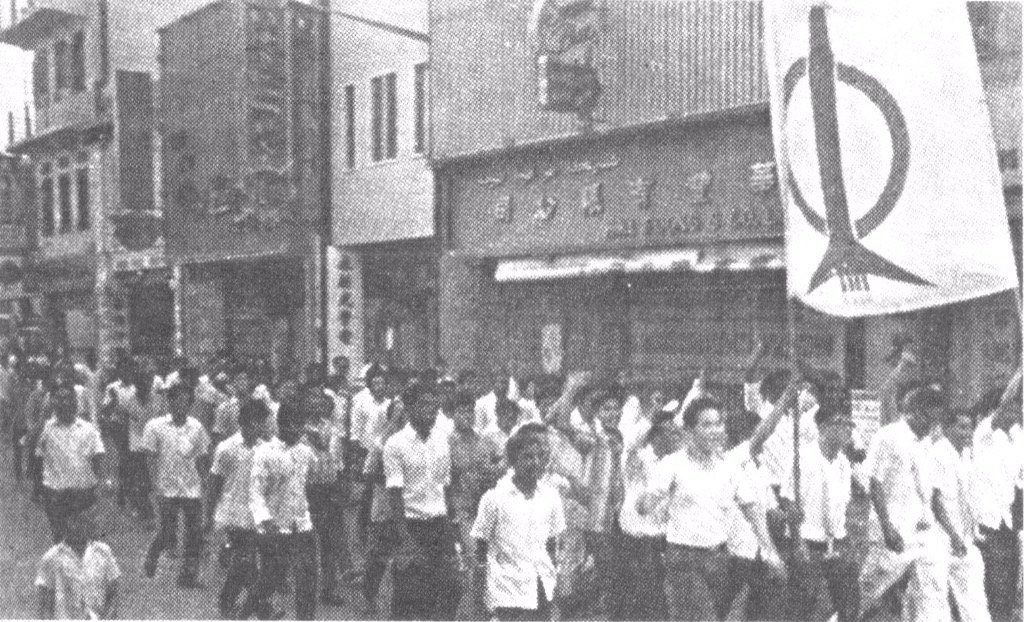

However, the situation reached a boiling point during the 1969 national election, when opposition (aka non-Malay) groups Parti Gerakan and Democratic Action Party (DAP) did much better than expected.

On 11 and 12 May, DAP and Gerakan supporters celebrated their electoral success with a large procession led by Gerakan leader David S. Vethamuthu.

However, what should have been a night of celebration was seen as highly provocative, with non-Malays taunting Malays. Although the Malays had won the overall election, the parade was seen as an attack on their political power.

As such, several members of the UMNO party announced that they would hold their own procession.

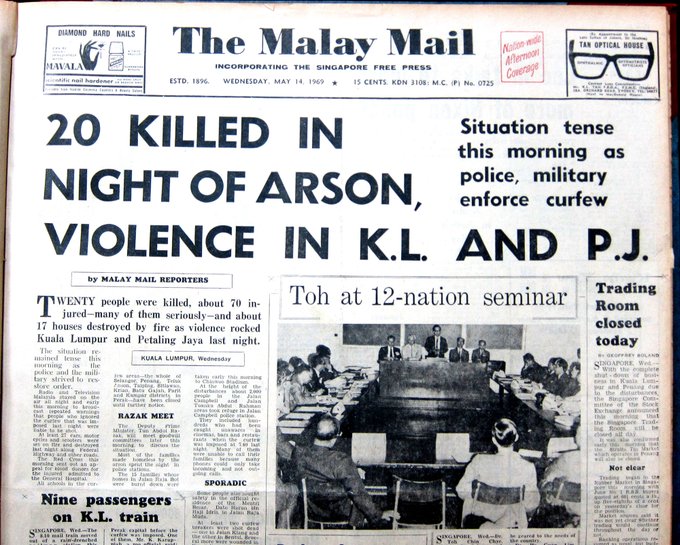

May 13

UMNO brought in thousands of Malays from rural areas into Kuala Lumpur, a predominantly Chinese city. The official plan was for them to gather at 7.30pm at Jalan Raja Muda, but even before they had finished gathering, it was clear that things were not going according to plan.

The first sign that things had gone wrong was a fist fight that broke out between a group of Malays and Chinese bystanders at around 6pm.

Both sides blamed the other for starting the fight, which quickly escalated from fists to bottle and stone throwing. The violence started to spread.

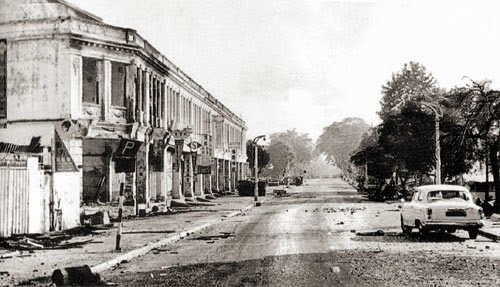

At 6.30pm, a group of Malays armed with parang and keris left the rally point and went into nearby Chinese neighbourhoods. They burned cars and shops, killing at least eight Chinese residents along the way.

Within an hour, the violence had spread all across the city. In Batu Road, Chinese and Indian shopkeepers worked together to chase off a Malay mob. In Chow Kit Road, armed gangsters patrolled the streets to scare away rioters, while other groups retaliated by killing any Malays spotted in Chinese areas.

At 7.35pm, a 24-hour curfew was announced for Kuala Lumpur. Police forces, who initially tried to use tear gas, were given shoot-to-kill orders.

At 10pm, the army was deployed into the rioting areas. They shot anyone who was still out in the open, though witnesses complained that several people had been shot while standing in their own doorways and gardens.

The Casualties

According to official reports, 196 people had been killed in the riots: 143 Chinese, 25 Malays, 13 Indians and 15 others.

However, foreign correspondents suggested that the real number was actually much higher considering how many people were classed as “missing” rather than dead.

Although the main incident took place in KL, similar instances occurred in other Chinese majority areas like Melaka, Perak and Penang. In June 1969, a new riot targeting Indians broke out in Sentul, killing 15 people.

Despite the army’s best efforts, the violence still continued for the rest of the week, causing many Chinese stores and houses to get burned down by Malay arsonists.

Those who’d lost their homes were sent to official refugee centres in different parts of town.

By the end of the week, the number of Chinese refugees had grown to 3,500 in Stadium Merdeka, 1,500 in Chinwoo Stadium and 800 in Shaw Road School. In contrast, there were only 250 Malay refugees sent to Stadium Negara.

Even a month after the riot, there were still over a thousand Chinese refugees stuck in Stadium Merdeka.

The Aftermath

Declaration of Emergency

Immediately after the riot, the government ordered a curfew throughout all of Selangor, bringing in 2,000 Royal Malay Regiment soldiers and 3,600 police officers to maintain control of the situation.

On 15 May, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong issued a Proclamation of Emergency, suspending Parliament and parts of the constitution.

A National Operations Council (NOC) was set up to restore law and order throughout the country. They immediately suspended the press and banned any foreign publications regarding the riots. Foreign reporters were regarded as “fake news” as they published articles that contradicted official reports and criticised the army’s racial bias.

In October 1969, the NOC released a report citing “racial politics” as the primary cause for the riots. The violence was blamed on Chinese Communists and “secret societies”:

“… the incitement, intemperate statements and provocative behaviours of certain racialist party members and supporters during the recent General Election; the part played by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and secret societies in inciting racial feelings and suspicion; and the anxious, and later desperate, mood of the Malays with a background of Sino-Malay distrust, and recently, just after the General Elections, as a result of racial insults and threat to their future survival in their own country.”

Rukun Negara

After the 13 May incident, the Rukun Negara was set up as Malaysia’s official pledge of allegiance in order to foster unity among the races of Malaysia.

The principles of the Rukun Negara were written up by the Majlis Perundingan Negara (MAPEN), headed by Prime Minister Tun Haji Abdul Razak bin Dato’ Hussein.

Today, the Rukun Negara is recited every week in Malaysian Primary and Secondary schools. More recently, in 2005 our government also made it compulsory to cite the pledge at official functions.

New Economic Policy

The riots of 13 May were seen as a result of high poverty rates and economical differences between the rural Malays and the urban Chinese.

As such, the New Economy Policy (NEP) was established to “tip the scales” by restructuring the economy and eliminating poverty.

Unfortunately, though it has achieved some success, the NEP has also drawn a great deal of criticism — the major one being that poverty is still a big issue even 50 years after the NEP was established.

In addition, many opposition members have pointed out the NEP policies are aiming for equality of results rather than equality of opportunity. Although some individuals received plenty of benefits, many others ended up falling through the cracks. Former Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj ibni Almarhum Sultan Abdul Hamid Halim Shah was especially critical about the NEP’s unbalanced implementation.

In his own words: “Some became rich overnight while others became despicable Ali Babas and the country suffered economic setbacks.”

52 Years Later

Next week will be the 52nd anniversary of the 13 May Incident.

Looking around, our country has changed completely in the past few decades. Today, Malaysia is a vibrant, rapidly developing country with more wealth and better standards of living than ever before.

However, even today, the rot of racism continues to lurk beneath the surface of our society. Many of us remain divided, more concerned with sticking to our own group than reaching out to others.

If we want to turn Malaysia into a modern, developed nation, then we must confront the spectre that is racism. Only together can the people of Malaysia advance. If we want to avoid the problems of the past, we must look beyond our differences and become a single, united nation.