The year is 1945, and great changes are happening all across the world.

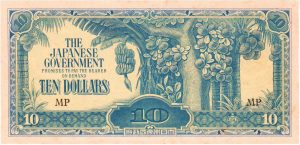

In Europe, Allied forces have taken over Berlin, ending the horrors of Nazi Germany. On the other side of the planet, America drops the world’s first nuclear bombs, breaking the Japanese’s will to fight.

And in Malaya, the triumphant British return, only to discover that their former servants are no longer willing to submit. The cry of Merdeka echoes throughout the land, a sign that things will never be the same again.

But while freedom may have seemed inevitable, the path to Malaysia’s independence would turn out to be more challenging than anyone might have expected.

Why Couldn’t We Become Independent Earlier?

In one word: racism.

The British government’s original plan was to set up a “Malayan Union“, combining the Federated and Unfederated Malay States with the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca. Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak were not included in this plan as it was believed that adding them in would make the nation too large and difficult to control.

As part of this plan, everyone living in Malaya — Malay, Chinese and Indian alike — would be granted citizenship. Everyone liked this idea except for the Malay Supremacist groups, who demanded a “Malaya for Malays” — a state ruled and controlled by Malays only.

One of these groups was the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), which was established in 1946.

The First Challenge: Communist Uprising

In the end, the Malay Supremacist’s protests grew so difficult to deal with that the British basically shrugged and just gave them what they wanted.

In 1948, the British dissolved the Malayan Union and replaced it with the Federation of Malaya. The Malay Sultans were restored to their former power while Penang, Malacca and Singapore remained in British hands.

The Malay Supremacists were pleased. After all, they had finally achieved what they wanted!

Unfortunately for them, it turned out that many people really didn’t like the idea of being turned into second-class citizens.

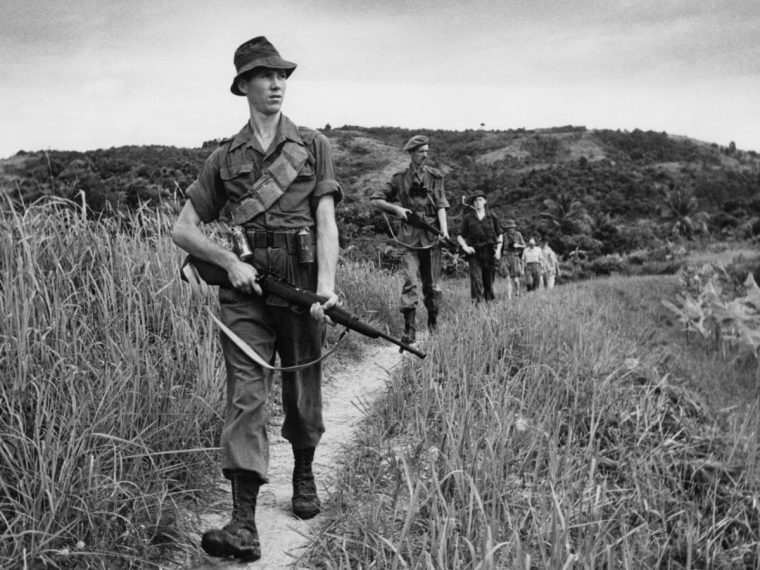

Shortly after the establishment of the Federation of Malaya, the tensions between the Chinese-led Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and the Malay-led government exploded into violence. Branding themselves the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the Communist fighters began a campaign of guerilla warfare that threatened to tear Malaysia apart before it could even truly begin.

Thus began the Malayan Emergency. There would be many other emergencies over the years, but the effects of this first emergency would shape our country to this day.

Why Was It Called An “Emergency”?

When the conflict began, the MNLA leaders declared that it was an “Anti-British National Liberation War”.

The British, on the other hand, insisted on calling it an “Emergency” instead — mostly for insurance purposes.

I’m serious. That really was the reason.

You see, insurance policies have a sub-clause which lets them avoid paying for “Acts of God” such as tornadoes, volcanic eruptions, etc. Many of these policies also include exemptions for events such as civil war, riots, and so on.

As such, the main reason why it was officially called the “Malayan Emergency” rather than something like “The Malayan Civil War” or “The Malayan War” was so that the British government could save some money.

Every time a tin mine, rubber plantation, manufacturing plant or other valuable piece of property was damaged or destroyed, the ones paying the bill would be some London insurance company rather than the Malay or British governments.

The End of Communism in Malaysia

Despite how long it dragged on, the Malayan Emergency was ultimately the first and only successful anti-Communist campaign in Asia. Every other instance has ended with either the Communist’s victory (Vietnam) or the splitting up of the original nation (North and South Korea).

The secret behind this success? Hearts and minds.

In January 1952, General Gerald Templer became Malaya’s new British High Commissioner. Realising that force alone wouldn’t be enough to defeat the Communists, he came up with a “Hearts and Minds” campaign.

While British troops continued to push the Communists deeper into the jungles, impoverished Malays and Orang Asli who lived in the area were provided with food and medical aid. Chinese Malayans were offered the right to vote, while captured Communists were treated mercifully and encouraged to change sides.

Over the next two years, it is believed that two-thirds of the Communist forces were wiped out. The number of incidents fell from 500 a month to less than a 100. Casualties among civilians and security forces dropped by nearly 80%.

Without Templer’s policies, it’s doubtful that the Emergency could have been won. Thanks to his efforts, the majority of MNLA’s forces eventually lost the will to fight on. By 1954, the Communists had been reduced from a massive army to a small gang of die-hard fighters.

The Second Challenge: Political Struggle

While the British were battling a Communist crisis, the Malayans were battling with a political crisis.

Simply put, everyone was angry at each other.

The Indians were mad because they felt that their people were being ignored by those in power.

The Chinese, on the other hand, were mad because they felt that their people were being oppressed by those in power. This was mainly due to the “Chinese new village” policy.

During the Emergency, over 400,000 Chinese were forcibly moved into newly built “villages” surrounded by barbed wire, watchtowers and guards who would shoot anyone trying to enter or leave without permission. While the idea was to cut off the Communists from any potential supporters, many of them were understandably furious about being locked up like this.

And the Malays? They were busy arguing over what they wanted an independent Malaya to look like. As usual, the ‘Ketuanan Melayu’ types made a big fuss. However, this time they received pushback from more moderate Malays who were sick and tired of their complaints.

The UMNO Drama

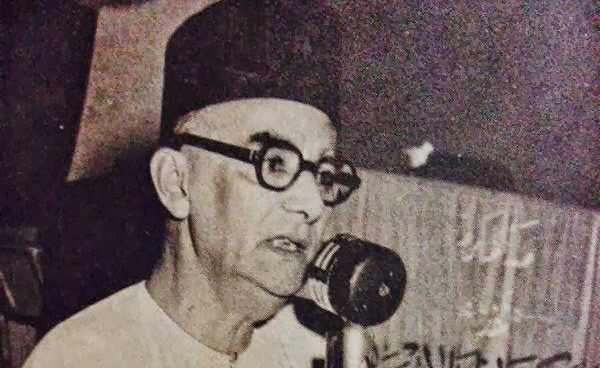

The situation came to a head during the UMNO General Assembly in August 1951, when UMNO founder Dato’ Onn Bin Jaafar left the party to create the Independence of Malaya Party (IMP), which was open to all races.

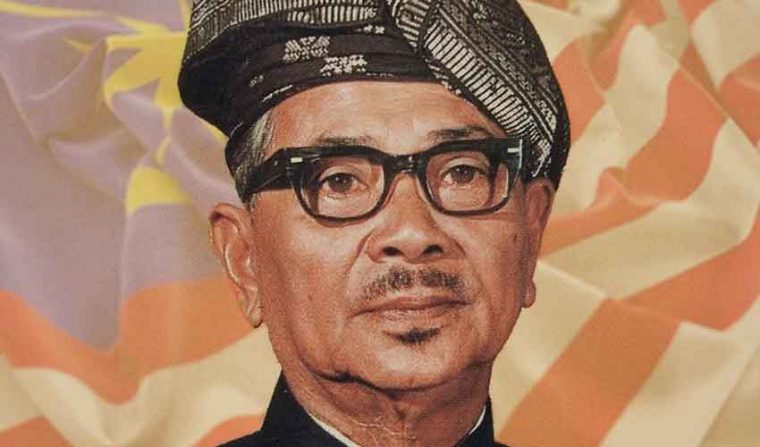

The person who replaced Onn Jaafar as UMNO President was a relatively unknown young man from Kedah who wasn’t actually that keen on taking the job. When UMNO Deputy President Abdul Razak first informed him of the nomination, the young man tried to refuse. It took some time, but in the end Abdul Razak was able to convince him that he was the best candidate for the position.

On 23 August 1951, Tunku Abdul Rahman was nominated as the President of UMNO.

The Rise of Tunku

Tunku’s first challenge was to defeat his predecessor, Onn Jaafar.

Onn Jaafar believed that Malaya could only achieve independence if they could show their unity. Thus, he created the IMP — a single political party made up of people from all races.

Tunku, however, took a different approach. While he understood the importance of racial harmony, he felt that each community should have their own political party to represent their unique interests.

In the end, Tunku’s ideals won.

Despite the protests of certain groups, during the 1952 elections UMNO worked together with the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA). The “Alliance” was a great success, and their candidates dominated the polls all across Malaya. The two parties were so successful that their leaders agreed to make the Alliance a permanent thing.

Despite Onn Jaafar’s best efforts, the IMP won only one seat in the 1952 elections. It was held by Devaki Krishnan — the first Malayan woman to be elected to public office.

Disappointed with his failure, Onn Jaafar dissolved the IMP in 1953. A year later, he would launch a new Malay-focused political party called Parti Negara. Although he hoped to become the “third force” behind UMNO and MCA, Parti Negara never gained any significant support and fizzled out shortly after his death in 1962.

The Father of Independence

With his position secure, Tunku turned his sights towards his primary objective: the independence of Malaya.

Tunku led a delegation to London in order to negotiate with the British government. Among them was the President of MCA Tun Dato Sri Tan Cheng Lock and the President of Malaysian Indian Congress Tun V.T. Sambanthan.

Together, this multi-racial group signed the Treaty of London 1956, the first concrete step towards Malayan independence. However, the official proclamation would be delayed for over a year due to logistical and administrative reasons.

At 9.30am, 31 August 1957, Tunku stood before a crowd of 20,000 and read the Proclamation of Independence, ending with the famous chant of “Merdeka!“

Independence Didn’t Solve All Our Problems

Malaya’s independence was an important moment, no doubt. Unfortunately, freedom comes with consequences. As Malaya’s first Prime Minister, Tunku had to deal with a dizzying range of challenges.

Some of these problems — such as the integration of Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak — were brand new. But his biggest problem, the one that plagued his rule and eventually brought him low, was something that was actually very old.

Yes, I’m talking about racism. Again.

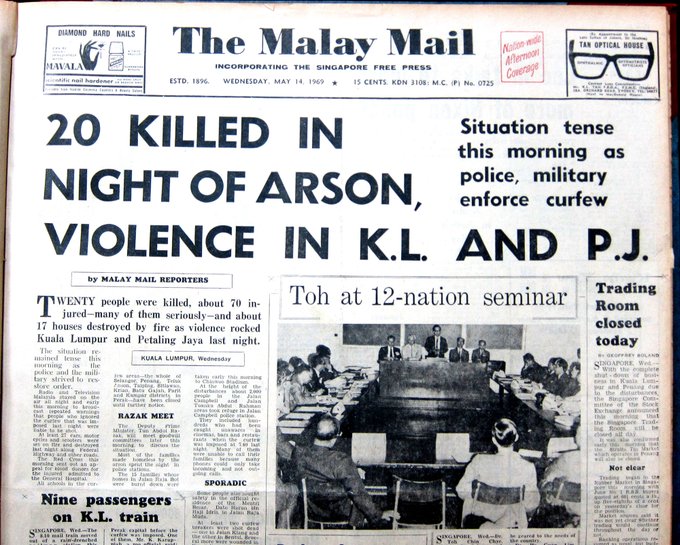

As the years passed, relations between the Malay and Chinese communities began to break down again. Despite his best efforts, Tunku was unable to prevent the tragedy of 13 May 1969. In the aftermath, Malaya’s Father of Independence was forced to resign, paving the way for a new government… one that would remain in place for many years.

To learn more about the events of 13 May, as well as some of the immediate aftereffects, check out:

Today in History: What Caused Malaysia’s 13 May Riots?