On this day I, like millions of other Malaysians, am enjoying a well earned rest for Malaysia Day.

But why is 16 September a public holiday? Don’t get me wrong, we all enjoy the break, but it’s important to understand the significance of what exactly Malaysia Day is and why it’s so influential to us.

Malaysia Day In A Nutshell

To put it simply, Malaysia Day marks the establishment of the Malaysian Federation. It was on this day that Malaya, North Borneo (aka Sabah), Sarawak and Singapore were all united into one country — Malaysia.

But if you’re a 90s kid like me, you might be asking “Well, if this is so important, why didn’t they teach us about Malaysia Day in schools? In fact, I don’t even remember having a Malaysia Day holiday!”

Well, that was probably because we didn’t have a Malaysia Day holiday back then.

While the date has always been historically important, Malaysia Day used to only be celebrated in Sabah and Sarawak.

However, everything changed on 19 October 2009, when former Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak decided to turn Malaysia Day into a nationwide public holiday as part of his 1Malaysia programme.

Najib believed that Malaysia Day would help to foster closer unity and understanding between the different races.

“We want the joy and sorrows of the people in Sabah and Sarawak to be felt by the people in the Peninsula,” he said during a question-and-answer session in Parliament.

“Therefore, I would like to announce to the people of Malaysia that the Cabinet has recently made the decision to celebrate Hari Malaysia on September 16 starting 2010.”

From Malaya to Malaysia

As we all know, Malaysia achieved independence from the British on 31 August 1957.

However, when Tunku Abdul Rahman made his famous speech and shouted “Merdeka!”, only the parts of the country that we now call Peninsula Malaysia became free. For six years, we were officially “Malaya” rather than “Malaysia”.

So what changed?

On 24 April 1961, Tunku received a message from Lee Kuan Yew, the Prime Minister of Singapore. In it was a very interesting proposal: the unification of Brunei, Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore into a single country.

But Why Did Lee Kuan Yew Want A Unified Malaysia?

Unlike Malaya, Singapore at the time was officially still considered a Crown Colony. However, it had its own internal self-government led by Lee’s People’s Action Party (PAP).

One of the reasons why Lee was interested in a unification was the strong historic and economic ties between Singapore and Malaya. He believed that Singapore’s future lay with Malaya and that the two nations would naturally unite over time (although soon, as we all know, he would eventually have a very big change of heart).

Aside from that, he was keenly aware that even if they became independent, Singapore was a small island that lacked the mainland’s abundance of natural resources. By merging the two nations, Lee hoped to create a common market that would benefit everyone.

Unfortunately, Not Everyone Was Happy With The Idea

Although Lee himself was all for unification, not all of his party members liked the idea.

In fact, the more pro-communist members of the PAP were strongly against the idea of Malaysia because they feared that they would lose influence — a fairly reasonable assumption given that Malaya was in the middle of the Emergency and was thus naturally suspicious of any communist supporters.

Meanwhile, in Malaya, Tunku was having his own party problems with the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO). The Malay-centric UMNO leaders were skeptical of unification as Singapore had a large Chinese population. They feared that adding Singapore would alter the racial balance of the country, weakening their own power base.

In the worst case scenario, it could create a government that was (gasp) not Malay!

Eventually, things came to a head when one of the pro-communist PAP ministers defected from the party — a move that threatened to bring down Lee’s whole government.

This frightened UMNO’s leaders. They realised that if Lee fell, he would be replaced by a pro-communist government. One that might end up aiding the communist insurgents fighting to take over Malaya!

Faced with this situation, UMNO finally changed their minds about the unification. While they still weren’t happy about adding all these new Chinese people to the population, it was better than having a new communist stronghold to the south.

Besides, the Bornean states had enough Malay people to cancel out Singapore’s Chinese majority, right?

Meanwhile, in Borneo…

Unfortunately, the people of Borneo were also rather suspicious of the whole unification thing.

In fact, some of them hated it so much that in December 1962, a group known as Parti Rakyat Brunei actually launched an armed revolt against Brunei’s Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III!

Although the revolt was quickly put down, it caused the Sultanate of Brunei to officially withdraw from unification talks. Even though the Sultan himself was rather sympathetic to the idea of unification, he feared that going through with it would only cause more violence in the future.

While the people of Sarawak and North Borneo never quite reached that level, they were determined not to become second fiddle to the more developed Malaya and Singapore. If there was going to be any unification, they wanted to be treated as equals.

As such, they demanded several terms from the federal government. North Borneo submitted 20 points, while Sarawak submitted 18 points.

Today, these are respectively known as the 20-point agreement and the 18-point agreement.

What Are These Points?

Although there are a few minor differences, both the 20 and 18 point agreements were written in order to protect the rights of those living in Sarawak and North Borneo.

To sum it up, the main points of this agreement involved:

- Religion

- Language

- Constitution

- Head of Federation

- Name of Federation

- Immigration Power

- Right of Secession

- Borneanisation of Public Service

- British Officers (aka: the Federal government couldn’t fire any British civil servants until there was a local replacement ready)

- Citizenship

- Tariffs and Finance

- Special Position of Indigenous Races

- State Government

- Transitional Period

- Education

- Constitutional Safeguards

- Representation in Federal Parliament

- Name of Head of State

- Name of State

- Land, Forests, Local Government, etc.

These agreements are a point of pride even to this day. In fact, some Sabahans and Sarawakians point to them as proof that their rights have been eroded over time.

Unification

Despite all these issues, the unification talks were settled by 1963.

The country of Malaysia would consist of Malaya, North Borneo (soon to be renamed Sabah), Sarawak and Singapore. The original plan for the official merger was on 31 August 1963 — the same date as Malaya’s independence day.

Unfortunately, it was not to be.

Both Indonesia and the Philippines objected to the formation of Malaysia. Philippines claimed that North Borneo actually belonged to them, while Indonesia accused Malaysia of “neocolonialism”, believing that the whole Malaysia thing was a sneaky plan by the British to take over the region… somehow?

In order to address these concerns, the United Nations sent a team to confirm whether or not North Borneo and Sarawak really wanted to join Malaysia. By the time the matter was settled, the original deadline had already been passed.

This is why Malaysia was officially formed on 16 September rather than 31 August.

And They All Lived Happily Ever After… Right?

To be honest, not really. While the unification was mostly a success, it also gave rise to many new issues.

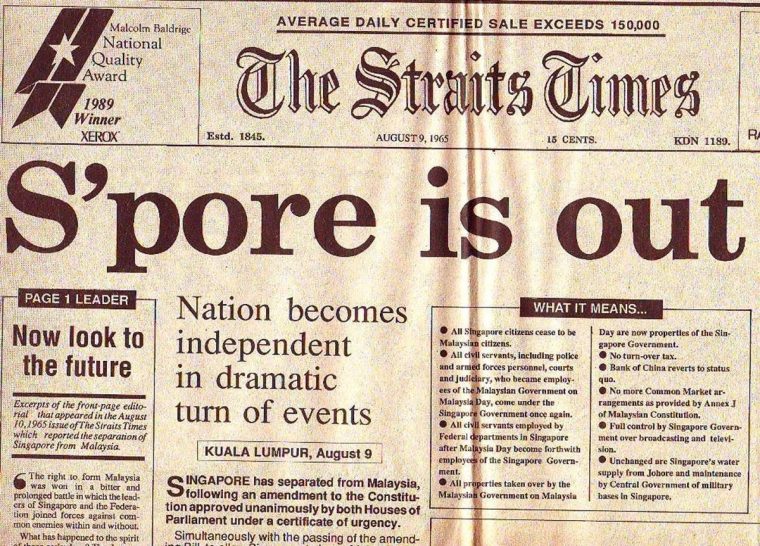

Over the next few years, the newly formed nation of Malaysia would face its fair share of challenges including the Separation of Singapore, the Konfrontasi and worst of all the 13 May Incident.

In time, it would overcome each of these challenges, growing into the Malaysia we all know and love today.

To learn more about some of the issues faced during Malaysia’s early years, check out:

Today in History: From Malaya to Malaysia